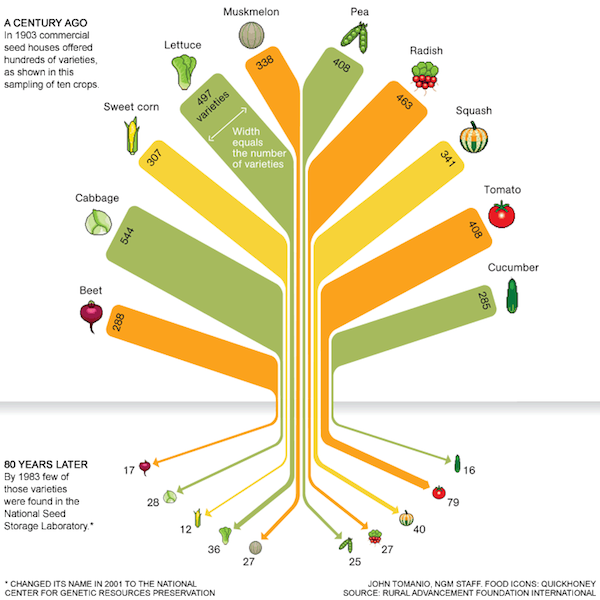

Food varieties extinction is happening all over the world—and it’s happening fast. In the United States an estimated 90 percent of our historic fruit and vegetable varieties have vanished. Of the 7,000 apple varieties that were grown in the 1800s, fewer than a hundred remain. In the Philippines thousands of varieties of rice once thrived; now only up to a hundred are grown there. In China 90 percent of the wheat varieties cultivated just a century ago have disappeared. Experts estimate that we have lost more than half of the world’s food varieties over the past century. As for the 8,000 known livestock breeds, 1,600 are endangered or already extinct.

Food varieties extinction is happening all over the world—and it’s happening fast. In the United States an estimated 90 percent of our historic fruit and vegetable varieties have vanished. Of the 7,000 apple varieties that were grown in the 1800s, fewer than a hundred remain. In the Philippines thousands of varieties of rice once thrived; now only up to a hundred are grown there. In China 90 percent of the wheat varieties cultivated just a century ago have disappeared. Experts estimate that we have lost more than half of the world’s food varieties over the past century. As for the 8,000 known livestock breeds, 1,600 are endangered or already extinct.

Heirloom vegetables have become fashionable in the United States and Europe over the past decade, prized by a food movement that emphasizes eating locally and preserving the flavor and uniqueness of heirloom varieties. Found mostly in farmers markets and boutique groceries, heirloom varieties have been squeezed out of supermarkets in favor of modern single-variety fruits and vegetables bred to ship well and have a uniform appearance, not to enhance flavor. But the movement to preserve heirloom varieties goes way beyond America’s renewed romance with tasty, locally grown food and countless varieties of tomatoes. It’s also a campaign to protect the world’s future food supply.

Six miles outside the town of Decorah, Iowa, an 890-acre stretch of rolling fields and woods called Heritage Farm is letting its crops go to seed. It seems counterintuitive, but then everything about this farm stands in stark contrast to the surrounding acres of neatly rowed corn and soybean fields that typify modern agriculture. Heritage Farm is devoted to collecting rather than growing seeds. It is home to the Seed Savers Exchange, one of the largest nongovernment-owned seed banks in the United States.

Today there are some 1,400 seed banks around the world. The most ambitious is the new Svalbard Global Seed Vault, set inside the permafrost of a sandstone mountain on the Norwegian island of Spitsbergen just 700 miles from the North Pole. The “Doomsday Vault,” as it is sometimes referred to, can hold 4.5 million seed samples.

In the 1920s and 1930s, Russian botanist Nikolay Vavilov headed an institute (now called the Research Institute of Plant Industry, in St. Petersburg) which housed his collection of 400,000 seeds, roots, and fruits – what amounted to the first global seed bank. Last winter, the Pavlovsk Station facility; part of the Vavilov Institute of Plant Industry in St. Petersburg, Russia, was threatened by building developers and still may be lost.

Sources and more reading:

National Geographic: Food Ark

Seed Banks – Our Insurance Policy for Food

Wikipedia: Svalbard Global Seed Vault