Wonder Bread or Wonderful Bread?

Chances are your family’s daily bread is just another item on your list when you shop at your favorite supermarket. Let’s take a closer look at what you’re bringing home; your bread may be “in disguise.”

It’s pretty clear that fluffy loaves of mass-produced soft, damp, nutritionally deficient, chemical-laced bread made in large industrial “bread factories” and sold in tightly sealed plastic bags contain additives and preservatives to make them easy to process and to give them a long shelf life. But what about the rest of those loaves lined up just asking to be dropped into your shopping cart?

Try this experiment – no, you don’t really need to buy 8 loaves of bread – and do your own comparison.

Make a stop at a large conventional supermarket, a natural foods market or co-op, and the closest artisan bakery you can find. At the very least, pick up a loaf of fluffy white bread, a loaf of “whole wheat” or “whole grain” bread in a plastic bag, a “baked in the store” loaf, an artisan loaf sold in an open paper bag, and – if you want to reach the full spectrum of taste and quality – a fresh loaf of naturally leavened artisan bread made with whole grain flour right from a craft bakery.

Now compare the weight, the color, the texture, and most of all – the flavor. What do you find? While the ranking below is purely subjective based on personal taste and perceptions, you will probably sort your selections in a somewhat similar fashion.

(Click on this image to see a larger version.)

Bread – the Good, the Bad, the Ugly

Exactly why is that loaf of fluffy “marshmallow” bread so consistently bland?

First, conventional wheat breeders seek genetic traits that result in higher and higher yields and better gluten for commercial bread making, while leaving out a key quality measure: flavor. When commercial supermarket bread includes high fructose corn syrup, salt, soybean oil, and sugar as standard ingredients (just read your nutrition labels), the flavor of the flour used in baking is just not that important.

Second, the bread-making process has been sped up to make a loaf of bread in as short a time as possible, reducing what traditionally took a day or two to an hour or two. It takes time for the dough to develop good flavor, so fast production means no flavor.

Just one step along the flavor/quality continuum are soft “whole wheat” or “whole grain” breads. In the last decade, even makers of refined white bread began to add brown coloring (caramel) and cellulose (wood fiber) to give the appearance of whole grain, high-fiber bread. In 2006, Wonder Bread was one of the first brands to introduce whole grain white breads made with an albino variety of wheat, that doesn’t have the “harsh taste” of whole red-wheat flour. These loaves are slightly – only very slightly – better flavor and quality.

Bread from supermarket “in-house bakeries” are loaves that are truly “in disguise.” Supermarkets very rarely bake bread “from scratch;” the loaves you find there are sometimes made from premixed ingredients or, more often, “baked in-house” from partially baked loaves shipped frozen and finished onsite. “Parbaking” is a process where the bread is mixed, kneaded, and baked until it is just about three-quarters finished, then frozen for shipping. The process sterilizes and stabilizes the loaf, but doesn’t give it the crisp brown crust.

Artisan loaves, especially if made with a natural leavening (like sourdough), have a firm crust and are weighty, flavorful, and have an intense aroma. Depending on the type or variety of grain from which the flour was ground, the flavor can vary considerably.

Much like wine and cheese, the flavors of grain – and the breads made from them – can be unique to a region or even a microclimate present on a group of farms. Small grain growers in Washington are experimenting with heirloom varieties. The grains and flours are sold locally to emphasize the concept of terroir: unique flavors developed from local soils and growing conditions.

The Wheat Family Tree

Humanity has been making and eating bread – at first unleavened and then later leavened with a variety of yeasts – for thousands of years.

The earliest known ancestral wheat species, the so-called “Neolithic founder crops” – einkorn and emmer – grew naturally all over the eastern Mediterranean region. They were “hulled” grains with a tight husk around each seed that had to be removed by parching or thrashing the grain.

Modern bread wheat with “naked” grains or those that separated easily from the husk was an early cross that appeared around 9,000 years ago. Early bread wheat containing enough gluten for yeasted bread dates from 1350 BC in Greek Macedonia.

Modern bread wheat with “naked” grains or those that separated easily from the husk was an early cross that appeared around 9,000 years ago. Early bread wheat containing enough gluten for yeasted bread dates from 1350 BC in Greek Macedonia.

The genus Triticum (wheat) is divided genetically into three groups:

- Wild and cultivated einkorn (diploids whose genes contain 14 chromosomes) is considered to be the “parent” wheat and was grown by man as early as 10,000 to 12,000 years ago.

- Wild and cultivated emmer and durum wheat (haploids – the 28 chromosome group). Durum, the world’s second most widely cultivated wheat, is primarily used to make pasta.

- Spelt and all bread wheat (hexaploids – the 42 chromosome group). Spelt is also a hulled wheat and common bread wheat is “free threshing,” that is, the hulls fall off at maturity. All hexaploid grains are domesticated; none have been found growing in the wild.

Today’s bread wheat has been one of the successes of selective breeding resulting in high grain yield, good quality for commercial baking, disease and insect resistance, and salt, heat, and drought tolerance.

Wheat came to America in the 16th century and thousands of landraces developed matching the grain to the local climate and growing conditions and exploding the number of wheat varieties to more than 40,000 currently identified by grain breeders. Wild and domestic grasses were crossed with domestic wheat to create new varieties such as Triticale (pronounced (trĭ tĭ cā’ lē), a cross between wheat and rye.

Taking Back Our Daily Bread

Bread was truly the “staff of life” for both peasants and noblemen for centuries. In the Middle Ages (the 5th through the 15th centuries), a majority of the population – mostly peasants – ate 2 to 3 pounds of bread a day.

Historically a wide variety of grains were used to make breads, depending on geographic location. Rye, wheat, and corn grew in different climates and bread had its own geography. Peasants ate heavy dark breads and the wealthy preferred bread made from white flour. The whiteness of the flour and the bread made from it were a sign of high social status because it was scarce and expensive.

In a reversal, the connotation of status based on the color of the flour used to make bread changed drastically in the late 20th century as whole grain bread was perceived as having superior nutritional value and white bread became associated with lower class ignorance of nutrition.

And, it is true, to fully benefit from high-tech food processing, mass production, long shelf life, product uniformity, even coloration, and soft texture, the production of wheat and bread stripped out most of the grains’ nutritional value.

When grain is milled into refined white flour more than 30 essential nutrients are removed, and only four of the original nutrients are added back in a process called “enrichment.” By the 1940s, malnutrition became so evident that flour manufacturers began adding vitamins and minerals as part of a government sponsored program to combat the high incidence of diseases such as Beriberi and Pellagra.

Let Us Eat (Real) Bread!

Marie Antoinette may – or may not – have said, “Let them eat cake!” when bread riots broke out in France in the late 18th century and launched the French Revolution. A new revolution needs to happen now.

Today’s consumers are still happily eating fluffy, enriched, cake-like white bread. It’s time to say, “Let them eat bread, real bread!”

Eat whole grain and artisan bread. Buy your bread from a small craft bakery or buy a small mill, grind your own flour, and bake your own bread. Seek out small local and regional grain growers. Celebrate the terroir of your daily bread!

Resources

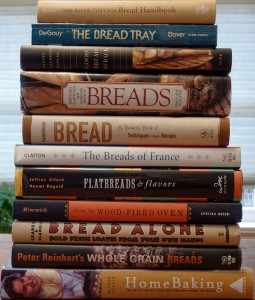

If you’re ready to experiment with baking your own bread, here are a few books you might read and websites where you can buy whole grains or flour.

Bread Books

The River Cottage Bread Handbook, by Daniel Stevens, Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall (Ten Speed Press)

Bread Tray: Recipes for Homemade Breads, Rolls, Muffins and Biscuits, by Louis P.De Gouy (Dover Publications)

Good Bread is Back, by Steven Laurence Kaplan (Duke University Press)

Bernard Clayton’s Complete Book of Breads, by Bernard Clayton (Simon & Schuster)

The Breads of France by Bernard Clayton (Simon & Schuster)

From the Wood-Fired Oven, by Richard Miscovich (Chelsea Green Publishing)

Bread: A Baker’s Book of Techniques and Recipes, by Jeffrey Hamelman (Wiley)

Flatbreads and Flavors, by Jeffrey Alford and Naomi Duguid (William Morrow Cookbooks)

Bread Alone, by Daniel Leader, (William Morrow Cookbooks)

Peter Reinhart’s Whole Grain Breads, by Peter Reinhart (Ten Speed Press)

Home Baking: The Artful Mix of Flour and Traditions from Around the World, by Jeffrey Alford and Naomi Duguid (Artisan Publishers)

Flour Water Salt Yeast, by Ken Forkish (Ten Speed Press)

Flour and Grains

Order online from any of these companies; all the grains and flours listed are organic.

Bluebird Grain Farms: Emmer Flour, Einka (Einkorn) Flour, Dark Northern Rye Flour, Hard White Wheat Flour, Hard Red Wheat Bread Flour, Emmer Pasta Flour – all organic (Washington only)

Bluebird Grain Farms: Emmer Flour, Einka (Einkorn) Flour, Dark Northern Rye Flour, Hard White Wheat Flour, Hard Red Wheat Bread Flour, Emmer Pasta Flour – all organic (Washington only)

Nash’s Organic Produce: Hard Red Wheat Flour, Soft White Wheat Flour, Annual Rye Whole Grain, Hard Red Wheat Whole Grain, Soft White Wheat Whole Grain, Triticale Whole Grain – all organic

Timeless Natural Foods: Purple Prairie® Barley Whole Grain, Emmer/Farro (Semi-Pearled) Whole Grain, KAMUT® (Semi-Pearled) Whole Grain, Durum-Iraq Whole Grain – all organic

Lentz Spelt Farms: Black Nile Barley Flour, Einkorn Flour, Emmer Flour, Spelt Flour, Black Nile Barley Whole Grain, Grünkern Whole Grain, Einkorn Whole Grain, Emmer Whole Grain, Spelt Whole Grain – all organic

Granite Mill Farms: Stone Ground Sprouted Hard Red Wheat Flour, Stone Ground Sprouted Soft White Wheat Flour, Stone Ground Sprouted Spelt Flour, Sprouted Hard White Wheat Flour, Sprouted Emmer Flour – all organic

Azure Standard/Azure Farms: Buckwheat Flour, Einkorn Flour, Sprouted Emmer Flour, Garbanzo Flour, Green Split Pea Flour, Hard Red Winter Wheat Flour, Sprouted Hard Red Wheat Flour, Hard White Winter Wheat Flour, Sprouted Hard White Wheat Flour, KAMUT® Flour, Lentil Flour, Millet Flour, Milo (Sorghum) Flour, Oat Flour, Whole Wheat Pastry Flour, Pinto Bean Flour, Quinoa Flour, Rye Flour, Small White Bean Flour, Spelt Flour, Triticale Flour – all organic

More Reading From GoodFood World

Reclaiming Farmland and an Ancient Grain

Dishing on Pollan’s Cooked

On the Road: Emmer – An Ancient Grain

Dryland Farmers – Eastern Washington and Northwestern Montana

How to Buy a Flour Mill: Check Craig’s List

On the Road: Historic Grist Mill, Thorp WA

Country Living Grain Mills: One Small Company’s Local Food Economy

When Did our Daily Bread Take a Wrong Turn?

Tall Grass Bakery: Let Them Eat Bread

Essential Baking: Seattle’s Biggest Small Bakery

Wheat Bread: a Baking Retrospective

Gail;

This was a fabulous article (Wonder Bread or Wonderful Bread), well researched, well written and very informative. I’ve had some communication with Dr. Richard Scheuerman, whom I presume you’ve interacted with who has engaged with Alex McGregor on ancient grain research. Your article filled in some of the blanks that I’ve been curious about since Dick turned me on to the “ancient grains” discussion.

Say, one other thing. I’ve run into a significant amount of science supporting that using starters instead of commercial yeast packs significantly reduces the gluten issue. In fact, a related Whole Grains Council article sites studies in which certain lacto-bacilli actually reduced the presence of gluten to levels that made the wheat based product virtually “gluten fee” (!!!??). I’m curious if, in your research, you’ve run into this. I’ve reached out to Dr. Barbara Rasco, WSU Director of Food Science for her input. I’ll pass anything along of value that I come up with.

Looking forward to meeting you folks at some point. Off to France July 19 for two weeks. So excited!!! We’ll reach out when I get back.

Hope your husband is feeling better!

Cheers!

Steve,

Thanks for the kind words! Grain, flour, and bread are food miracles and fascinating topics.

As far as wild yeast (sourdough “starters”) versus commercial yeast, I’m not a chemist so I can’t speak to what actually happens with the gluten. That said, I do know that I’ve read the fermentation process does change the gluten structure slightly and may make it more digestible.

I would be very careful and avoid saying that it will “reduce the presence of gluten to levels that made the wheat-based product virtually ‘gluten-free’.” Anyone who suffers from celiac disease should avoid wheat gluten in all forms and from all “members of the wheat family.”

I’d be very interested in what Dr. Rasco has to say about it.

Travel safely!

Gail N-K

Managing Editor, GoodFood World