1988, January: We hosted a Sustainable Farming Association winter house meeting. These were held in the evenings at the homes of various members, where we could have discussions on what things worked best, and learn from each others experiences. It was a very supportive, helpful, and rapidly growing group.

February: We had a new sheep shearer this year. When our old shearer was three weeks late with the shearing the previous year, and showed up the day after lambing had started, that was the beginning of the end. Although he had been my shearer for nearly 20 years, and was a very good shearer, he was perpetually late, and always had a million excuses. I valued his skills enough to put up with his idiosyncrasies, but finally last year was the straw that broke the camel’s back, and I said, “No more!”

Having lambing going on while shearing was also in progress was horrible! The ewes had already been stressed during the last three weeks of their pregnancy by being crowded together in their full fleeces, when they should have been shorn, and were huge with lambs. Movement was difficult, and one of my favorite older ewes, “Gogo,” came down with Ketosis, or pregnancy toxemia, caused by not being able to compete well at the feed manger due to the crowding. The disease results from mobilization of the ewe’s own body fat to provide energy for growth of the fetuses during the final weeks of pregnancy. I kept her alive by administering propylene glycol orally and injections of glucose subcutaneously.

Gogo went down shortly before going into labor, and could not get up. Once labor began and progressed far enough for me to intervene, I had to pull both lambs. They were huge and the first one was presented backwards. The second had one front leg turned back under its body, so it was a difficult delivery, and Gogo could not help much. She never made it up again, although she continued to eat for about a month, then worsened. When it was obvious she would not recover, I called my vet and had her put to sleep. Lambing continued to be challenging that year.

So in 1988 we had a new sheep shearer, and he had two teenage sons who also sheared. All were excellent shearers, and showed up on time a month before lambing commenced. They bought our wool, paid a good price, and our shearing problems were solved.

March: Lambing went much more peacefully this year, although not without its usual challenges. One thing was different this time – “Big Mumbo” slowed down a bit, and only delivered triplets! “Big Jumbo” also had triplets, as did several other ewes, but the majority had twins, very few singles, and the flock’s lambing average increased to 204%. Lambing average is the number of lambs saved per ewe per year, not the number born.

April: Shortly after lambing was over, I was at our local health clinic for some reason, which I don’t recall. We had recently acquired a new British doctor, whom I had not yet met. I was sitting in the waiting room when the new doctor came striding past, glanced at me briefly, and in a minute or so later he came striding back. He came directly up to me and inquired as to whether I had lambs, and whether I would sell him one. Being British, he loved to eat lamb, but had been hard pressed to find “good lamb” in this area. However, someone had put a bug in his ear that I raised excellent locker lambs, so he wanted to buy one.

I told him I would be delighted to sell him a lamb, but they were only a few weeks old and would not be ready for sale for several months. Suddenly, I had a serendipitous moment… there was that quintuplet ewe from last year who was such an outstanding specimen and outshone her two sisters. (Remember?) She did not get bred last fall and now she was showing definite ram-like tendencies! So, I broached the possibility to the good doctor; if he would consider a yearling ewe, rather than a lamb, I had one available. I was trying to explain nicely that she was a bit different, when he immediately said, in his direct British way, “Oh, a butch lady sheep; I’ll take her!” So that was that! He also put in an order for a lamb as soon as they were ready, and he became one of my best lamb customers.

Over time, we had some interesting, though out of the ordinary, consultations. One was the time I stabbed myself in the calf of my left leg with a small pen knife. I had been driving across the hill pasture in my small Datsun truck (a stick shift), where the pasture had been grazed and then mowed to get rid of a few thistles. I suddenly spotted one thistle that had been knocked over, but not completely cut off.

Not wanting to see it survive and start a new crop of thistles, I stopped the truck, got out, and having my pen knife in my jeans pocket, I proceeded to use it to saw away at the stout thistle stem. I was using a lot of pressure in the effort, and suddenly the blade cut through the thistle, and wound up in the calf of my left leg.

It was not a terribly deep wound, but was bleeding profusely, my sneaker was full of blood, and not wanting to bleed all over my truck, I decided I could drive home with the drivers’ door open and let my leg hang outside the truck. Of course, I had to pull it in to use the clutch and shift gears, but I got home.

I cleaned up the wound a bit, put a bandage over it, and decided I better go to the clinic and get a tetanus shot. Of course, I had to explain to the doctor how this accident came to happen. But, I became one of his most intriguing patients when I showed up with a case of “Orf,” better known as “sore mouth” – a sheep disease!

I contracted it from a bottle lamb that nicked an index finger on my right hand with a sharp tooth when I was bottle feeding her. I didn’t think much about it at the time, but in a few days the finger became extremely sore. At this point I noticed that the bottle lamb had a small pustule on its lip, and a light came on in my brain, “I have sore mouth on my finger!”

The finger began to throb, to the point where I spent a sleepless night, and decided it was time to go see the doctor about this. When I told him what it was, he said, “We don’t know how to treat a sheep disease! But Mayo will!” I impressed him by knowing the correct name of the affliction, which was “Contagious Ovine Ecthyma,” and he got on the phone to the Mayo Clinic.

They went to work on the problem, and in a short time they came up with the name of the drugs that were needed to cure me. In due time, I was cured of the problem and relieved of the pain of one very sore finger.

Some time after this, I learned that bottle lambs are more susceptible to sore mouth than other sheep, as when they nurse from a bottle, their lips can become abraded from contact with the hard back of the nipple, especially when they are vigorous nursers. This makes them vulnerable to the sore mouth virus, which is present in the soil.

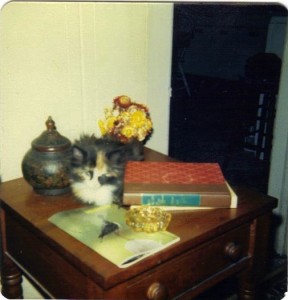

May: My young friend, Diane, who had spent a lot of her childhood days here, riding ponies with Lisa, brought me a beautiful long haired Calico kitten. She was known variously as “C C,” for Calico Cat, or “ZhuZhie,” Hungarian name for “Sweetheart.”

She gave us many years of pleasure, and lived to a ripe old age. I can see her yet, parading through the house with her gorgeous plume of a tail held aloft like a banner. She grew to be a huge cat, and looked very much like a “Maine Coon” cat.

1988 was an excellent year for sales of our breeding stock, 79 ewe lambs and 7 ram lambs were sold to other breeders, 9 locker lambs were sold to individuals, and the remaining wether lambs were sold on the Corn Belt Tele-Auction.