Then things got more complex. As communities grew, consumers moved into towns and villages. Around the perimeter growers raised the food that was sold to the residents of those towns and villages. The farmers brought their own products to market and sold them directly to consumers.

A supply chain with two links!

![]()

As time passed and cities grew, things got more complicated – a LOT more complicated. Today, in the early 21st century, somehow we still want to believe that the supply chain – the link between the growers and the consumers – is just as simple as it used to be, way back when!

Here is how we see the contemporary food system. A miracle occurs somewhere between the grower and our table and the products get from plow to plate by magic!

Somehow in our delusion, we imagine the farmer pulling his or her truck up behind the supermarket and unloading baskets of fresh fruits and vegetables or sides of beef and pork into the open arms of the retailer and his staff. And, frankly, the bigger the supermarket, the more likely there will be signs, photos, and even wall-sized murals showing farmers and ranchers smiling as they offer their vegetables and fruit or stand with an arm around the neck of a sleek beef cow.

Well, folks, I hate to tell you, it ain’t so. Time to hear the real story.

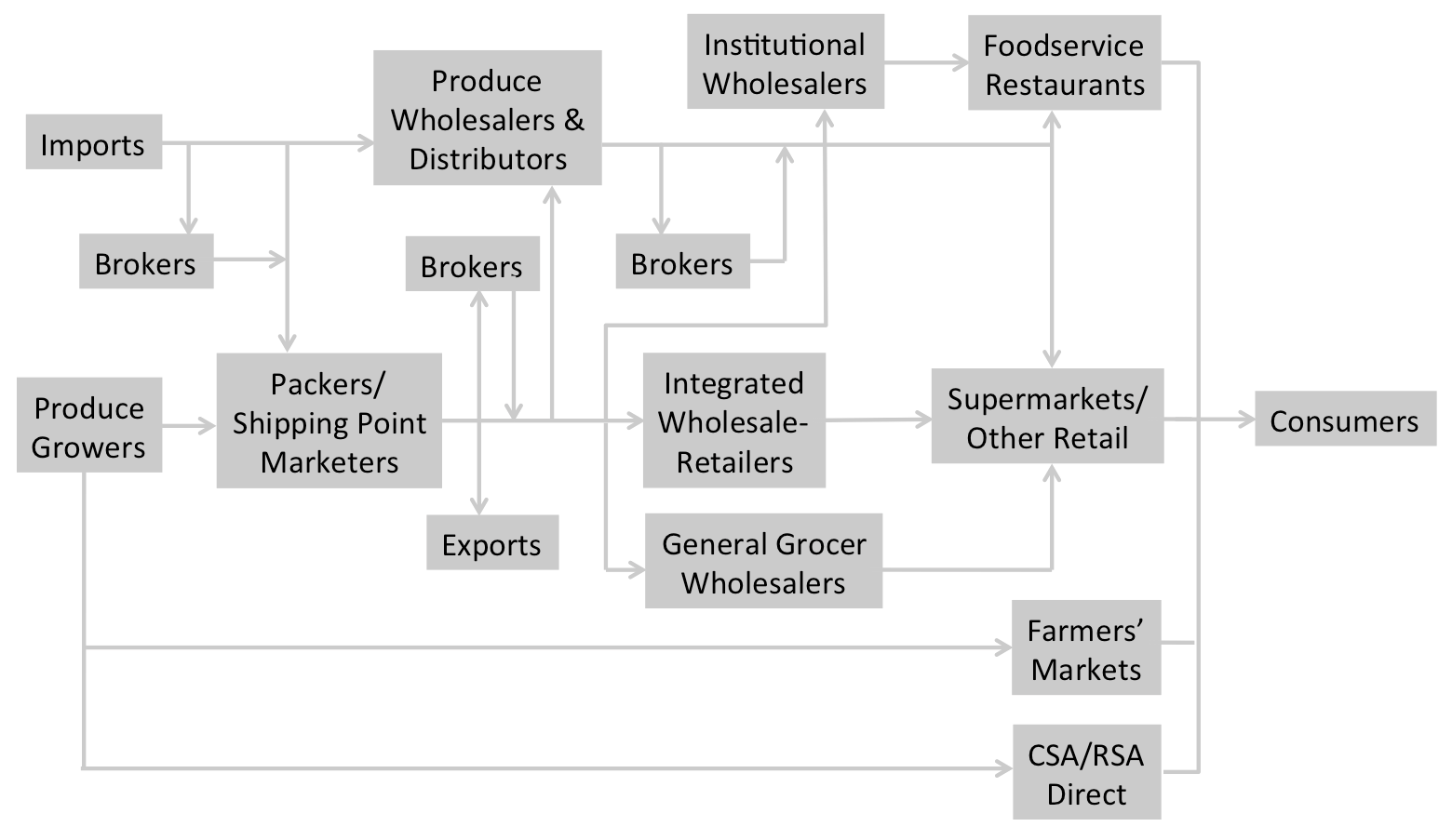

Meat, dairy, fish, grain – each one has a specialized supply chain to get food from the producer to the consumer. A specialized and complex supply chain. Let’s take a closer look at just one of the multitude of food supply chains – the produce system – and see what’s behind that magic box.

What once was a simple connection with one or two stops along the way, has become a spaghetti-like tangle of links, cross-links, and hand-offs to get fresh fruits and vegetables to your plate.

Each one of the nodes in the network removes another layer of transparency and makes knowledge of the grower more and more difficult. The connection with the farmer and his farm has been lost. And the larger grower/packers – that is, large farms that have their own packing operations – sell directly to “integrated wholesale/retailers” like Safeway, Krogers, and Wal-Mart, and have created their own simplified supply chains. Those huge companies have their own wholesale functions to redistribute product to the individual retail stores. Big supporting bigger!

Miles and Miles

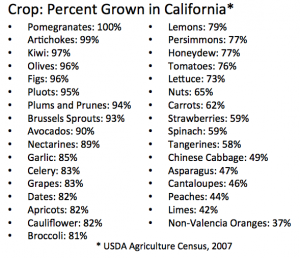

There have been studies conducted across the US to estimate the distance – the number of “food miles” – that your food travels to get to your plate. Of course, that number depends on where you live in the country and what food products you are tracking! If you live on the East Coast or in the Midwest, for example, your domestically grown fruits and veggies travel a lot farther than if you live on the West Coast. After all, about 50% of our fruits, vegetables, and nuts are grown in California.

A 2008 study by the National Sustainable Agriculture Information Service reported that fresh produce travels an average of 1500 miles or more, but the destination point in the paper was the Chicago Terminal Market. So much for produce grown in North America. If you live in Seattle and pick up apples from New Zealand in your favorite store’s produce section, the trip is more than 7000 miles, and those table grapes from Chile? They clock about 6400 miles.

Why the Long Trips?

Our food system has changed substantially over the last 50 years. Globalization; centralization of the food industry and concentration of the food suppliers to fewer, larger suppliers; the completion of the North American interstate highway system; and low-cost air freight, have all contributed to the availability of a wider variety of produce all year ’round, regardless of the season or place of origin.

It’s not just the high cost of energy and “embedded carbon” from the construction of highways and manufacture of trucks and airplanes that we should be concerned about, but also the loss of the nutritive value in the food itself. The farther food travels and the longer it takes to get to your table, the more the freshness declines and the more nutrients are lost. After all, once fruit is picked, it is dead – and it slowly spoils. To combat the natural decomposition process, more and more fruits and vegetables are engineered for a long shelf life, sacrificing taste and nutrition for preservation. Green tennis ball tomatoes, anyone?

Local and Regional Production – It’s a Good Thing, But…

Getting local and regional produce into the food system is not particularly hard if you are a large producer with connections to the established food distribution system, but it is a real challenge for small and mid-sized producers. As retailers grow, their connections to the distribution network become increasingly formalized and vertically integrated. Regional and national chains have longstanding direct relationships with larger farms, with “grower-shippers,” and with big production co-ops.

Small, diversified farms can’t offer the volumes, particularly over an entire growing season, that large mono-cropping growers can. And the cost of packing, cartons, and trucking to distribution centers adds an additional financial burden. By joining together as producer co-ops, small farmers can share the cost of marketing and equipment (including trucks) to access the distribution system.

Buyers who are seeking to connect to the small local production network have a variety of issues to deal with:

- Volume, price, and uniformity requirements – small, diversified farms are at a real disadvantage when compared with large integrated operations.

- The labor cost – and challenge – of managing too many vendor accounts. Very small, independent retailers may buy from several hundred individual producers; some from as many as 1000. Large grocery chains want to simplify, simplify, simplify. Buying through a limited number of large wholesalers and distributors is much more efficient, however efficiency can mean the illusion of more choice, when in actuality there is less diversity.

- The need for a consistent ordering and distribution system.

- Food safety requirements that include third-party certification.

While buying local is an admirable goal, we simply cannot grow bananas or citrus in the Pacific Northwest. And you’d find it really, really difficult to buy pomegranates and avocados grown in Washington, but we do a pretty good job with many of the other fruits and vegetables during the summer season. Come winter, however, our short days make it impossible to grow much of anything except in a greenhouse with supplemental lighting. As a result, local is seasonal in most parts of the region.

A Regional Distributor That Works

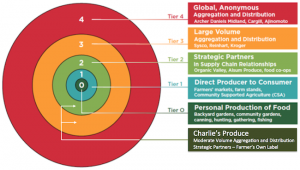

From Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) and farmers markets to supermarkets and “Big Box” stores, there is a continuum of relationships between consumers and the businesses that grow, process, distribute, and market their food. And as we’ve seen, the food system is more complex than just local versus global and artisan versus industrial; there are diverse food businesses that are part of the relationship between consumers and producers all along the supply chain.

Charlie’s Produce, headquartered in Puget Sound, is an example of a regional produce wholesaler/distributor connecting the links between small growers and retailers and food service in the Pacific Northwest. Charlie’s Produce was founded in 1978 by Charlie Billow and Ray Bowen (both of whom still work for the company), and Terry Bagley (recently retired).

The three formed Triple B Corporation to make their dream of a wholesale produce company come true. Put together three men and a couple of trucks and you get Charlie’s Produce! One of them would take orders on the phone while the other two delivered vegetables and fruit to restaurants and small markets in the Seattle area.

Charlie, Ray, and Terry prided themselves in finding something unique for area chefs. Known for having something different, Charlie’s would have special items like baby carrots and fresh herbs – something that was not at all common then, as it is now.

Charlie, Ray, and Terry prided themselves in finding something unique for area chefs. Known for having something different, Charlie’s would have special items like baby carrots and fresh herbs – something that was not at all common then, as it is now.

Today, Charlie’s maintains four distribution centers (Seattle, Spokane, Portland, and Anchorage) comprising 130,000 square feet for produce, 12,000 square feet for processing, and 75,000 square feet for dry, freeze, and chill grocery lines. An employee-owned company, Charlie’s is a large regional employer and has more than 1000 people on staff.

Local Production – Local Support

Charlie’s Produce is a combined conventional and organic produce distributor and has been committed to buying local since the company’s launch. Nearly 40 conventional growers in Washington – 15 of those in Puget Sound – supply fruits, vegetables, and floral products.

Responding to consumer trends for more and more organic produce, in 1991, Charlie’s acquired Farmers Own Organic Produce, a brand that contracts with 15 Washington growers to sell their products. Farmers Own is a marketing service that advises growers, supplies branded boxes and other packing materials, and transports produce from the farm. And as part of the marketing service, Farmers Own helps growers plan production calendars, teaches bagging and packing techniques, and offers farm tours for buyers who want to make personal connections with the farmers.

Responding to consumer trends for more and more organic produce, in 1991, Charlie’s acquired Farmers Own Organic Produce, a brand that contracts with 15 Washington growers to sell their products. Farmers Own is a marketing service that advises growers, supplies branded boxes and other packing materials, and transports produce from the farm. And as part of the marketing service, Farmers Own helps growers plan production calendars, teaches bagging and packing techniques, and offers farm tours for buyers who want to make personal connections with the farmers.

Farmers Own growers are spread across Washington; the farms range from 10 to 1000 acres and are located an average of 127 miles from Seattle. Fifteen other organic Washington and Oregon farmers also have distribution agreements with Charlie’s through Farmers Own.

Charlie’s is committed to buying local because it is good business:

- Buying local reduces food miles.

- Buying from local growers supports the local economy.

- Buying local keeps land in agricultural use, benefiting the environment and protecting open space.

- Buying local organic avoids synthetic fertilizers and pesticides, reducing the toxins handled by farm workers and by shoppers and their families.

- Buying local ensures a secure source of food with less reliance on produce from out of state or outside the country.

- Buying local satisfies consumer demand for local and organic food.

As the demand for local and organic fruits and vegetables continues to grow – sales of organic produce increased more than 400% between 1997 and 2008 – it will be companies like Charlie’s Produce and marketing groups like Farmers Own that will make the connections between small local producers and the regional distribution network.

The conflicts between globalization of our food system, limited energy resources, and the challenges of climate change, are driving a shift from hierarchical distribution networks to a new kind of distribution system, a system that more directly connects growers and consumers. We need to shorten the supply chain, reduce the time and distance food travels, and deliver products grown locally (or at most regionally) by farmers that consumers can know by name. We will also see a new emphasis on restoring our local and regional agricultural eco-systems and discovering new varieties of plants and animals that are locally adapted.

The Story Continues…

This is the first segment in a continuing series of articles exploring the complexity of the food system – and it IS complex! Meat, fish, grain, and dairy all have their own unique supply and distribution networks and at GoodFood World we are exploring them all.

The issue of food safety, now garnering more and more attention thanks to online publications like Food Safety News, is an integral part of every supply chain and distribution network. We are closely following the new food safety rules just published for comment – the Proposed Rule for Produce: Standards for the Growing, Harvesting, Packing, and Holding of Produce for Human Consumption and the Proposed Rule for Preventative Controls for Human Food: Current Good Manufacturing Practice and Hazard Analysis and Risk-Based Preventative Controls for Human Food. As the rule-making process moves forward we will highlight the effects of new – and existing – rules and how they are applied, including labeling.

Because labor, worker welfare, and pay issues are often overshadowed by other economic considerations – profitability, for example – we continue to explore the development and implementation of fair trade standards being established domestically and around the world.

And finally, because included in any supply chain is the unpleasant and often unaddressed element of waste, we will be working with organizations that are creating solutions to eliminate some of the 40% of edible food that is lost or wasted in the US between the field and the fork. That food waste accounts for 25% of all freshwater used in the US, 4% of US oil consumption, $750 million in disposal cost, and 33 million tons of landfill waste that contributes to greenhouse gas emissions, particularly methane.

Keep reading and join in the conversation!

Additional Reading

Local Food Systems – Concepts, Issues, and Impacts (PDF)

Why Local Linkages Matter (PDF)

Food Systems for Rural Futures (PDF)

The Role of Global Producers in Increased Consumption of Unhealthy Commodities (PDF)

Land To Mouth – Understanding the Food System (PDF)

Can Western Washington Feed Itself? (PDF)

UW – Food Distribution Systems (PDF)

Local Food Supply Chains (PDF)