Our Daily Bread

Bread went from being a major part of our ancestors’ food intake to being a very small part of the food we eat today.

Heavy, rich, and nutritious bread was once a daily staple; today commercial “industrialized” bread is produced in fully-automated factories and is full of chemical additives, preservatives, and too much salt, and has too little nutritive value.

What went wrong?

Humanity has been making and eating bread – at first unleavened and then later leavened with a variety of yeasts – for thousands of years. It was about 10,000 years ago that man began to domesticate the cereal grains that would become bread.

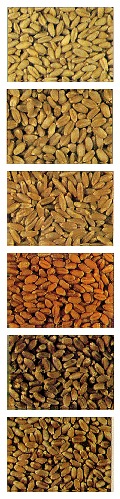

The earliest known ancestral wheat species – einkorn and emmer – grew naturally all over the eastern Mediterranean area. They were “hulled” grains with a tight husk around each seed that had to be removed by parching or thrashing the grain. Modern bread wheat with “naked” grains or those that separated easily from the husk was an early cross that appeared around 9,000 years ago.

Today’s bread wheat has been one of the successes of selective breeding resulting in high grain yield, good quality, disease and insect resistance, and salt, heat, and drought tolerance.

Bread was truly the “staff of life” for both the peasant and the nobleman for centuries. In the Middle Ages, for example, a majority of the population – mostly peasants – ate 2 to 3 pounds of bread a day.

Historically a wide variety of grains were used to make breads, depending on geographic location. Rye, wheat, and corn grew in different climates and bread had its own geography. Peasants ate heavy dark breads and the wealthy preferred bread made from white flour. The whiteness of the flour and the bread made from it were a sign of high social status because they were scarce and expensive.

As the quality and variety of foods improved and other sources of protein became available, the amount of bread consumed began to drop. By 1880, daily diets included only about 1 1/3 pounds of bread and, just a century later, in 1977, that amount dropped to a little over 6 ounces of bread a day. Today, even with government recommendations of 6 to 8 ounces of “grain equivalents” a day, most Americans are likely eating half as much bread every day as they did just 40 years ago.

In a reversal, the connotation of status based on the color of the flour used to make bread changed drastically in the late 20th century, at least among the elite, as whole grain bread was perceived as having superior nutritional value and white bread became associated with lower class ignorance of nutrition.

And, it is true, to fully benefit from high-tech food processing, mass production, mass marketing, long shelf life, product uniformity, even coloration, and soft texture, the production of wheat and bread stripped out most of the grains’ nutritional value.

When grain is milled into refined white flour more than 30 essential nutrients are removed, and only four of the original nutrients are added back in a process called “enrichment.” Malnutrition became so evident that, in the 1940s, bread manufacturers began adding vitamins and minerals as part of a government-sponsored program to combat the high incidence of diseases such as Beriberi and Pellagra.

Industrialization

As early as the mid-19th century, bakers were attempting to speed up the production of bread. Even the fastest traditional methods could take up to 24 hours to produce a finished loaf. The Aerated Bread Company, London, perfected a method of combining flour and water supersaturated with carbon dioxide under pressure.

As early as the mid-19th century, bakers were attempting to speed up the production of bread. Even the fastest traditional methods could take up to 24 hours to produce a finished loaf. The Aerated Bread Company, London, perfected a method of combining flour and water supersaturated with carbon dioxide under pressure.

When thoroughly mixed, the spongy dough was ready for the oven. No yeast and no time needed for the yeast to ferment. The entire process took less than 30 minutes.

The “aerated bread” resulted in such fluffy loaves of bread that a satiric science fiction story was published in 1958, Bread Overhead (Fritz Leiber) which described the resulting product as containing “No yeast creatures in your bread!” The bread was so light that they filled “the midwestern skies as no small fliers had since the days of the passenger pigeon…” and could be sold as “bread balloons” on strings in a cluster.

By the early 1950s, American industrial bakeries were mass-producing bread and bakers discovered that the addition of certain chemicals and enzymes – bread “improvers” – to the dough could shorten the process to two hours.

Bread improvers boosted the amount of amylase and protease enzymes that develop the flavor and strengthen the gluten artificially, giving the bread a better structure and retaining more of the gas produced by the yeast.

While the ingredients of improvers can vary largely depending on their use and the manufacturer, a few important ingredients are found in all improvers:

- Ascorbic acid – used to strengthen the gluten

- Hydrochloride – gluten softening and clearing

- Sodium metabisulfate – gluten softening and clearing

- Ammonium chloride – food for yeast

- Phosphates – food for yeast

- Amylase – enzyme used to break down starch into simple sugars, thereby letting yeast ferment quickly

- Protease – enzyme used to improve extensibility of the dough

Because these additives are used in very small quantities they are usually distributed in a soy flour filler.

In the UK in 1961, another major “advance” in commercial bread making happened with the development of the Chorleywood Bread Process, which incorporates intense mechanical working of the dough to again reduce the fermentation time. The process of high-energy mixing means allows the use of inferior grain, and is used around the world in large bread “factories,” though not as much in the US as in other countries.

By the early 70s, as the natural food movements and the “second wave” of food co-ops spread beyond the “back to the earth” idealists, consumers began to look for healthier and safer foods, including whole grain and naturally leavened bread. However, today we are seeing even small “look-natural” bakeries making imitation artisan and sourdough bread by using chemical additives in prepared mixes which contain most or all of the dough’s ingredients.

Back to the Future

In response to mass-produced soft, damp, nutritionally-deficient chemical-laced bread, a demand – “craze” some would say – for artisan, home-style breads started in the 1990s. And by 2005, even makers of refined white bread began to add brown coloring (caramel) and cellulose (wood fiber) to give the appearance of whole-wheat, high-fiber bread. In 2006, Wonder Bread was one of the first brands to introduce whole grain white breads made with an albino wheat variety of wheat, that doesn’t have the “harsh taste” of whole red-wheat flour.

First let’s get the mystery of Wonder Bread – that mysterious loaf of “marshmallow” bread – cleared up. Exactly how is it possible to make such a smooth loaf with no holes? Here’s your answer!

Franz Bakery – the Big Guys, “Your Neighborhood Bakery”

Large automated bakeries, like Franz Bakery in Seattle (part of United States Bakery), literally go from flour to packaged bread with no human hands ever touching it.

Large automated bakeries, like Franz Bakery in Seattle (part of United States Bakery), literally go from flour to packaged bread with no human hands ever touching it.

With inputs of more than 1 million pounds of ingredients every week, Franz Bakery offers 2000 different products to restaurants, institutions, and retailers in the Pacific Northwest. In 2005 (the latest date numbers are available), Franz mixed 183.5 million pounds of bread dough, 112.2 million pounds of dough for buns, and more than 3.4 million pounds of dough for cookies. That’s a lot of dough!

While the following video was not filmed at Franz Bakery, it follows a description of Franz’ process almost step-by-step.

Bread Made OF Montana

A home-based cottage food bakery producing naturally leavened breads and baked goods sold at Helena’s Farmers Markets and direct-to-consumer through a bread CSB – Consumer Supported Bakery.

Made with flour from Montana-grown grains.

An “on farm” bakery producing naturally leavened breads made of heirloom grains grown and milled on the farm and with flour from other Montana-grown grains.

Bread available in the on-farm store and in Great Falls at the Farmers Market and select retailers.

Resources:

Domestication of Plants in the Old World, Daniel Zohary and Maria Hopf, Oxford University Press, 2002

A History of Food, Maguelonne Toussaint-Samat, Wiley-Blackwell, 2009