The Phoenicians are credited with many things, but delivering the gift of wine to the shores of southern Europe is something for which mankind will always be thankful. Like the modern-day Lebanese, the fearless seafaring Phoenicians had an urge to meet distant horizons with zeal and brought grape growing and wine making in their wake.

Today, Lebanon’s 4000 plus commercial grape farmers continue these ancient traditions and produce approximately 117,000 metric tons (MT) of grapes each year.

Lebanese grape cooperative Rachaya Al-Foukhar is located in southeast Lebanon on the edges of the great Bekaa Valley. The area is arid and sparsely populated, and its inhabitants regularly face hardships associated with the isolation. Since the civil war erupted in the mid seventies, the village’s population has slowly emigrated to Beirut to find better economic opportunities.

For the grape farmers, the geography is both a blessing and an obstacle. Because of the heat, farmers can produce high quality grapes before the rest of Lebanon’s grape farmers, but due to the isolation, they cannot reach sustainable markets and stay profitable.

“When we drive to the wholesale market located in Ferzol, almost two hours away, the sun and heat end up hurting the quality of our grapes,” explains Ibrahim Jradi, the cooperative’s manager.

In 2014, the USAID-funded Lebanon Industry Value Chain Development program partnered with Rachaya Al-Foukhar’s 40 grape farmers to develop a strategy that would allow the farmers to reach new markets without compromising quality.

Under the partnership, the USAID program and the cooperative developed a cold chain strategy that significantly reduces post-harvest losses and enables the farmers to reach not just Ferzol but markets further afield. Under the strategy, the partners invested a total of $100,000, of which USAID covered 67 percent and the cooperative the rest.

In 2015, the cooperative first established a climate-controlled facility to sort, store and pack their grapes. The facility—which has the capacity to package and store 10 MT of grapes—created employment for 12 people and allowed Rachaya Coop to offer cold storage services to area grape growers. The cooperative also acquired a refrigerated truck to transport their fruit to distant markets.

Finally, the cooperative purchased better packaging made from cardboard instead of plastic, and received training on post-harvest handling and cold storage to ensure the grapes are maintained at appropriate temperatures from harvest to market.

“If we want to reach high-end retail channels, we needed to change how we treat and present our grapes. The cold chain is critical to maintaining quality. Cardboard packaging is grape-friendly and looks more professional,” explains Roger Bassit, President of the cooperative.

The USAID program takes a market systems approach that is intended to allow farmers, processors and traders to improve the profitability and quality of agriculture products all along the value chain.

Last July, following the initial harvest, the cooperative used the cold storage and the next day delivered over two tons of grapes to Ferzol’s wholesaler marketplace. In the early season of July, Rachaya had the only grapes at the market, and they were fresh.

“We didn’t expect them to sell so quickly. In fewer than 20 minutes they were gone,” says Ibrahim Jradi. Over the next month, the cooperative sent once, sometimes twice, daily shipments to the market. In total, the cooperative sold 120 tons worth $260,000 in 2015.

The success has had a wider effect on area farmers, who have seen the group’s strong sales and begun recuperating their lands to grow grapes. Since the historic summer, Rachaya has already added seven new members. Phoenicians may have brought grapes to the rest of the world, but the grape farmers of the Rachaya cooperative are now bringing the country’s best grapes to the people of Lebanon.

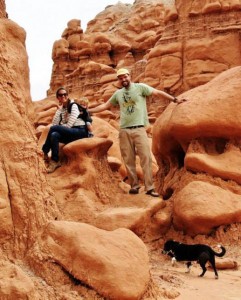

About Nicholas Parkinson (Nico Parco)

Nicholas is an NGO writer currently based in Botswana. He has worked on agriculture-focused projects in Ethiopia, Uganda, Zambia, Somalia, and Liberia. He specializes in NGO documentation, communications, and PR, and teaches local writers how to create attention-grabbing stories for their NGOs.

A journalist, climber, husband, and father – as well as companion to Mino, a black and white dog – Nico has lived in several countries and speaks several languages. Today he focuses on writing, documenting, and story telling.

Here is a link to Nicholas’ GoodFood World articles and commentary.