Waste:

To waste: to use or expend carelessly, extravagantly, or to no purpose (verb)

Waste material or product: discarded as no longer useful or required (adjective)

A waste: the act of expending something carelessly, extravagantly, or to no purpose (noun)

Waste – an alternative definition:

“Waste” from one process is the “input” for another process. In a system of closed loops feeding on one another, the waste – or unused output – from one process provides input nutrients for the next. In nature, there is no waste. A dead tree or animal provides nutrients for new life and new growth.

It’s the 21st Century and one would think that by now human beings would have figured out creative and efficient ways to produce sufficient healthy and nutritious (good) food to feed us all and to eliminate costly and destructive food waste.

It turns out that we not only haven’t figured it out; the whole process is getting more and more problematic and the amount of food waste – at least in the United States and other developed countries – is increasing.[1]

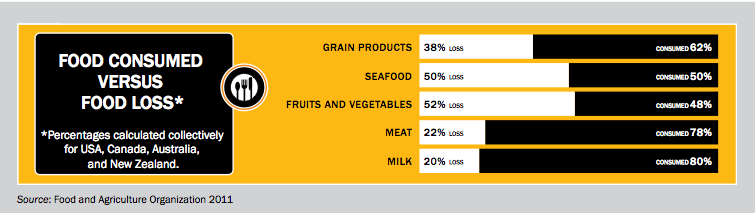

As much as 50% of the edible food products grown and produced in the United States are lost, discarded, or “wasted” from the farm to the fork. And more than a quarter of those food products are discarded after they are purchased in retail stores or restaurants.

What we consider food waste requires a huge amount of energy and water – in the form of human labor, petroleum-based fertilizers and pesticides, and water for production and processing. Much of it could be avoided, and what remains unconsumed can be turned into nutrient-rich compost. Food waste is not something to be disposed – carelessly, extravagantly, or as having no purpose – it is a source of nutrients for sustainable food production, for healthy agricultural systems, for life itself.

Food Waste in the 21st Century

Americans throw away a lot of food, but sometimes looking at an image of a big pile of food can distance us from the real problem. Here’s how you can bring it home. Try this experiment:

Americans throw away a lot of food, but sometimes looking at an image of a big pile of food can distance us from the real problem. Here’s how you can bring it home. Try this experiment:

- Pull out a carton of eggs to make breakfast. Wait… take 3 of those eggs out of the carton and throw them away.

- Fire up the grill and make up four nice quarter pound patties to fix for supper. Wait… throw one of those burgers away.

- Bake a lovely apple pie and sit down to enjoy it after dinner. Wait… cut a quarter of that pie out of the dish and throw it away.

In America, we don’t just throw food away; we throw a LOT of food away – carelessly and extravagantly! Every time you grab a snack, prepare lunch or dinner, or sit back for dessert, cut it into quarters and imagine throwing one quarter away. THAT’s how much food we waste.

In this article we examine the causes and sources of food waste, the ways urban food waste is handled, the benefits of collecting and using food waste to make compost, and the value of compost in agriculture and urban gardens.

Throw It “Away”

A study by the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), Global Food Losses and Food Waste, carefully examines food losses along the entire food supply chain, from the farm to the consumer’s table. The result? Approximately “one-third of food produced for human consumption is lost or wasted globally, which amounts to about 1.3 billion tons a year.”

Many of us imagine that we who live in high-income industrialized nations are better at avoiding and preventing waste. It turns out that per-capita, we who live in the “North” – that is, the northern hemisphere where most of the industrialized countries lie – waste more food than people living in poorer, developing countries.

Clearly, in parts of the world where the cost of food is high – poorer, less developed countries – more care is taken with food in the household. In countries where food is cheap (in the US we spend about 10% of our household dollars on food), we have more and we waste more.

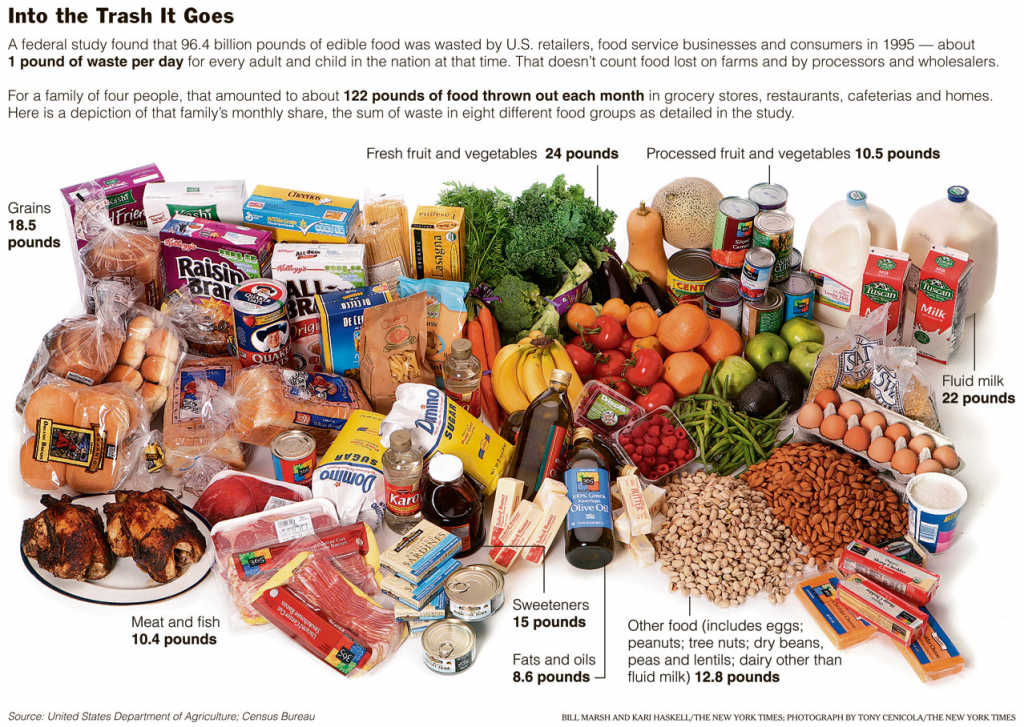

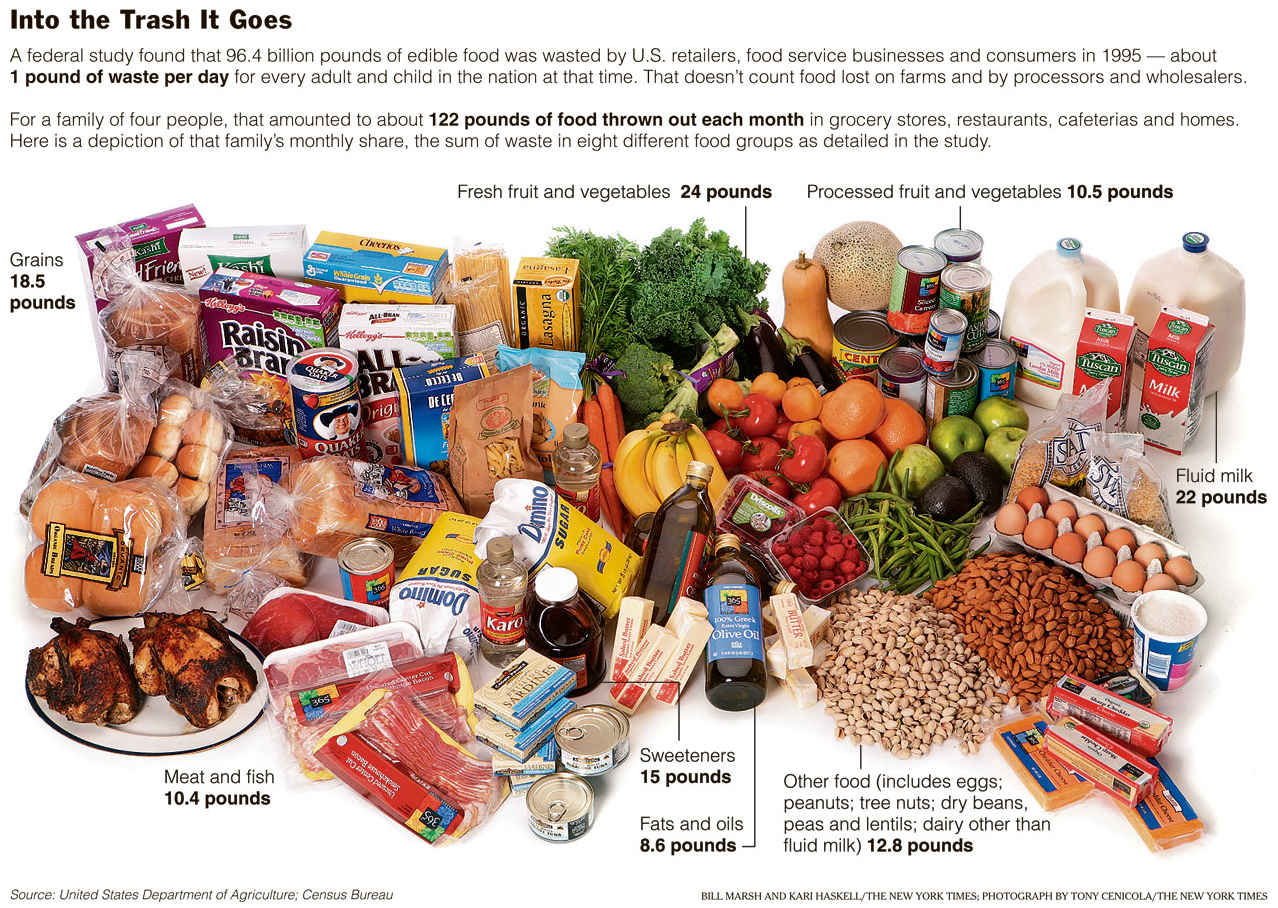

The FAO estimates that consumers in North America and Europe waste between 200 and 250 pounds of food, per person per year.[2] And the USDA is even more pessimistic; the estimate is about 350 pounds per person, annually. (See the image above.) Depending on locale and income level, the amount of food wasted could be 2 or 3 times that.

Not only do American consumers waste a lot of food, both at home and in restaurants, the amount of food wasted has continued to grow since the 1970s, by nearly 50%. Today, according to the Natural Resources Defense Council, American families throw out approximately 27% of the food and beverages they buy – at an estimated cost of $1,365 to $2,275 annually for a family of four. Half or more of the produce and seafood we buy goes to waste.[3]

Where Does It Go?

We think we throw it “away” – but there is no away to throw it to. Well, actually we throw it IN, mostly into municipal landfills. In 2010, the EPA estimated that Americans generated about 250 million tons of trash and recycled and composted over 85 million tons of this material, equivalent to a 34.1% recycling rate. On average, we recycled and composted 1.51 pounds out of our individual waste generation of 4.43 pounds per person per day.

We think we throw it “away” – but there is no away to throw it to. Well, actually we throw it IN, mostly into municipal landfills. In 2010, the EPA estimated that Americans generated about 250 million tons of trash and recycled and composted over 85 million tons of this material, equivalent to a 34.1% recycling rate. On average, we recycled and composted 1.51 pounds out of our individual waste generation of 4.43 pounds per person per day.

Before recycling and composting, about 13.9% of the municipal waste stream consists of food waste. Multiplying that back against our “individual waste generation” indicates that Americans each dispose of about two-thirds of a pound of food waste daily.[4]

Let’s take another run at this. The USDA estimates that each person wastes about 350 pounds of food annually, the FAO estimates consumers waste between 200 and 250 pounds per year, and the EPA estimate of food in the solid waste stream is approximately 225 pounds. Using the EPA percentages of solid waste, food waste, and recycled/composted waste, we also compost about 76 pounds of food waste a year.

Like any statistical averaging, the numbers disguise the fact that active composting is disproportionate depending on location and circumstances: households living in their own homes with the space to compost may have the opportunity to do so, yet we are finding the number of home owners actively composting is decreasing in reflection of the convenience of curbside food and yard waste bins.

Regional Handling of Solid Waste, Including Food Waste

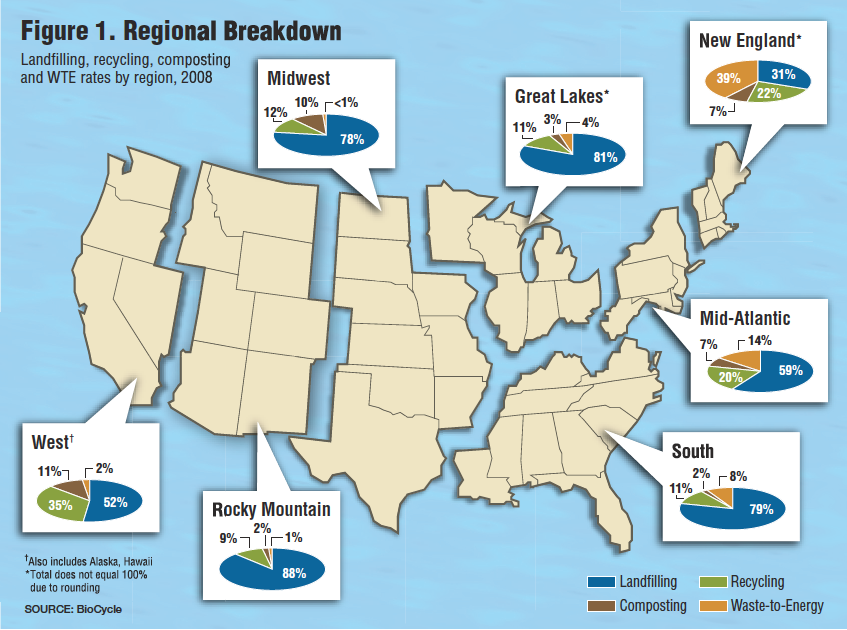

Looking at all these numbers in aggregate causes us to miss some important details. As we try to dig into the numbers to find out what might be happening to food waste in the municipal system, we find that 10 of the 50 states and District of Columbia either have no composting system for organic waste or roll their composting numbers into their recycling numbers. The State of Garbage in America report, conducted every two years by Columbia University[5], tells us that nationally we compost just over 6% of our solid waste.

And the amount of waste – including food and yard waste – that is composted varies greatly from region to region. From as little as 2% in the South and Rocky Mountain regions to 11% in the Western region, which includes Hawaii and Alaska. Washington State, for example, recycles and composts about 8.6% of the municipal solid waste generated.

In Puget Sound, Food Waste Is Not Wasted

Nearly all households (99%+) in King County are able to recycle food scraps and food soiled paper in curbside food and yard waste bins. Before the institution of curbside collection, food waste comprised nearly one-third of the residential garbage in the county.

By the end of 2011, Seattle residents living in single family, multi-family, and multiplex dwellings were required to sign up for organics (food and yard waste) collection or request an exemption if they had backyard food waste composting.

Has the new requirement been effective? Well, on one hand, yes. In 2010, a City of Seattle Home Organics Waste Management Survey[6] reported that 87% of residents put food waste in their yard waste container for municipal pickup. That number was up from 49% in 2005. The primary method of food scrap disposal identified in 2010:

| Food and yard waste container | 72% |

| Regular trash | 10% |

| Home composting | 10% |

| Garbage disposal | 5% |

While a very small portion of food waste enters the waste water system through garbage disposals, King County Water Treatment District (WTD) reports that, “the net cost of treating food waste entering our large sewers and treatment facilities is minimal. The food wastes create both a cost (primarily energy consumed to treat the food waste at our plants) and a benefit (biogas energy recovered from digestion of the food waste), which tend to offset each other.”[7]

The addition of food waste to yard waste containers and an increase in collection from once every two weeks to weekly have had considerable effect on home composting of both types of waste. Compare these two survey results describing home composting behavior:

| 2010 | 2000 | |

| Yard waste only | 16% | 19% |

| Food waste only | 6% | 4% |

| Both yard and food waste | 14% | 27% |

| Neither yard nor food waste | 64% | 50% |

In 10 years, the percentage of people composting food waste actually went up a little, but the percentage of people composting both yard and food waste at went down by nearly half. Households composting NEITHER yard or food waste rose from 50% to 64%. From the perspective of City and County utilities, the collection program is a vast success, however that same program is instrumental in the removal of valuable nutrients and biomass from lawns and gardens.

In a twist of irony, 95% of the City of Seattle survey respondents had yards, 80% said they had lawns, and 74% had a garden; gardeners had both flower gardens (61%) and food gardens (48%). Why is that ironic? Simple – these same people are paying the City to collect a valuable nutrient source from their homes and yards and then buying either synthetic fertilizer or composted organic matter to amend their soils and treat the lawn and garden.

Yes, In My Back Yard (YIMBY)

Composting: The biological reduction of organic wastes to humus. “Let’s just say that compost and composting are, like water and air, essentials of life.”

The Rodale Book of Composting (Rodale Press, 1992)

We live in a small house in the city and grow some of our own food. Blessed with a wider-than-normal city lot, we have room for fruit trees, vegetable gardens, berry bushes, and lots of borders of lettuce and leafy greens. We also have three different kinds of compost bins and a free-form compost pile. Unlike most of our neighbors, we compost all of our grass clippings and most of our yard waste and all of our food waste.

That said, we also live in a part of the city that, 175 years ago, was an old-growth forest growing on a series of eons-old sand dunes. Fast-forward to the 21st century, after the forest had been clear-cut and the thin layer of topsoil had been stripped off in the post-World War II building boom, and we live on a sand pile. It’s a sand pile that requires huge amounts of organic matter to make it fertile enough to grow healthy food, because the heavy moisture of Puget Sound continually leaches the nutrients away.

Two people and one city lot simply do not create enough food scrap, grass clippings, and “yard waste” to make sufficient humus for “feeding” a hungry sand bed. We do generate a lot of compost, but we need much more. Our solution? Yes, we still purchase compost. Lots of compost…

Our choice for locally produced organic compost is Cedar Grove Compost. And with Cedar Grove, we close the local loop. Scroll back to the discussion about Seattle’s and King County’s programs for curb-side collection of food and yard waste… Where does most of that organic waste go? To Cedar Grove, where it is ground, mixed, sifted, aged, and turned into premium organic matter for gardeners and farmers.

Cedar Grove collects food waste from restaurants, retailers, food processors, and institutional food service and serves as a collection point for City and County-contracted residential organic waste collection companies. The company processes 350,000 tons of organic matter every year. (Read our profile of Cedar Grove Compost here.)

Waste Not – Your Options

Whether you live in a house on a city lot or in the suburbs or in an urban apartment with little access to green space of any kind, you can still do your part to reduce – and, yes, compost – food waste.

The Natural Resources Defense Council recommends:

- Shop Wisely—Plan meals, use shopping lists, buy from bulk bins, and avoid impulse buys. Don’t succumb to marketing tricks that lead you to buy more food than you need, particularly for perishable items.

- Buy Funny Fruit—Many fruits and vegetables are thrown out because their size, shape, or color are not “right.” Buying these perfectly good funny fruit, at the farmer’s market or elsewhere, utilizes food that might otherwise go to waste.

- Learn When Food Goes Bad—“Sell-by” and “use-by” dates are not federally regulated and do not indicate safety, except on certain baby foods. Rather, they are manufacturer suggestions for peak quality.

- Mine Your Fridge—Websites such as www.lovefoodhatewaste.com can help you get creative with recipes to use up anything that might go bad soon.

- Use Your Freezer—Frozen foods remain safe for a long time. Freeze fresh produce and leftovers if you won’t have the chance to eat them before they go bad.

- Request Smaller Portions—Restaurants will often provide half-portions upon request at reduced prices.

- Eat Leftovers—Ask your restaurant to pack up your extras so you can eat them later. Freeze them if you don’t want to eat immediately. Only about half of Americans take leftovers home from restaurants. Suffice it to say, “eat leftovers” also applies to the food you cook in your own kitchen!

- Compost—Composting food scraps can reduce their climate impact while also recycling their nutrients. Food makes up almost 13 percent of the U.S. waste stream, but a much higher percent of landfill-caused methane.

- Donate—Non-perishable and unspoiled perishable food can be donated to local food banks, soup kitchens, pantries, and shelters. Local and national programs frequently offer free pick-up and provide reusable containers to donors.[8]

And finally for those of you who want to compost in your backyard or even in your apartment, here are some suggestions:

- Check with your city or county solid waste utility to find out if you can get free or low cost compost bins.

- Shop at your neighborhood garden center, farm supply dealer, or online. There are literally dozens of different compost bin shapes and sizes available.

- Apartment dwellers: if you have a balcony so much the better, but it is possible to buy an “indoor” compost bin that can accommodate food scraps from a small family. Check with a garden center or shop online.

Here’s what we use our compost for:

Recommended Reading

Waste: Uncovering the Global Food Scandal by Tristram Stuart

American Wasteland by Jonathan Bloom

Designing America’s Waste Landscapes by Mira Engler

Holy Shit: Managing Manure To Save Mankind by Gene Logsdon

The Soul of the Soil by Joe Smillie and Grace Gershuny

Teaming with Microbes by Jeff Lowenfels, Wayne Lewis, and Elaine Ingham

The Post Carbon Reader by Rchard Heinberg and Daniel Lerch

Pardon the typos & grammar errors.

Thank you for this in depth article. Composting aside, one thing that really stood out for me was the statistic that more than half of produce purchased gets thrown in the trash.

Why is that? Hmmm…I’ve got an idea. Because it tastes bad. Because more and more, fruit (& vegetables) are bred (not GE)for shelf life, bright color, and uniformity of shape. They are being grown to look good, and in the process, become devoid of juice, texture and taste. In the case of strawberries for instance, they are grown to be large so it’s easier and more cost effecive to pick them and ship them accross the country.

I know for a fact my own Mom complains about buying produce (especially fruit, and then just throwing it out because it never ripens, or just rots immediately. It’s likely been shipped from halfway around the world, out of season, or picked within the US from distant farms long before they should be.

I have a hard imagining anyone throwing out freshly picked berries,peaches or apples or cukes from a local farm’s roadside stand. They usually taste too darned good, and the problem is often the reverse. Buy enough to have something leftover when you get home!

Just another reminder of how creating a plethora of year round global produce doesn’t guaranty a bounty worth eating. Perhaps compost is it’s only hope.

Ina,

You’re so right about sexy produce – sort of like the “Ladies of the Evening,” all show!

Just about once a year we get suckered into buying a carton of early strawberries from California, and I swear I’ll never do it again. They’re bright red, big as golf balls, white inside and taste like cardboard!

I started calculating the weight of our food scraps yesterday and we seem to have so much – mostly peels: apple, banana, onion, grapefruit…

This morning I made candied grapefruit peal out of the two halves left from breakfast… I’m now considering saving the apple peels and juicing them! Talk about OCD!

On the other hand, if we bought our peas and carrots frozen in bags, we wouldn’t have had carrot peels last night after supper. So do I create the waste here, or do I fob it off on the food processors who cut up the carrots for me?

It’s really a quandary, isn’t it?

We’ve decided to forgo the processed/prepared food and turn our food scraps into compost to put back on our garden.

Greens, leeks, and all kinds of other goodies are out there to be picked right now!

Take care, eat well, be well!

Gail N-K