Copyright by and reproduced with permission from Devon Peña, Professor of Anthropology,

University of Washington, Seattle WA.

Moderator’s Note: It is my privilege this time of the year to present the work of my undergraduate students at the University of Washington. This year I am presenting a series of outstanding blogs by students enrolled in my course on Environmental Anthropology.

Moderator’s Note: It is my privilege this time of the year to present the work of my undergraduate students at the University of Washington. This year I am presenting a series of outstanding blogs by students enrolled in my course on Environmental Anthropology.

The large lecture format course introduces students to the field of environmental anthropology, which includes the study of Ethnoecology – the knowledge of ecology developed by indigenous and other traditional place-based peoples. The course also examines contributions from the fields of critical political ecology, which focuses on the role of science in the politics of environmental law, policy, and social movements.

Finally, we study aspects of environmental history, which focuses on the role of human societies – both small- and large-scale – in processes of ecological change and includes analysis of the history of ideas about the quality of the human-environment relationship. Like the class, these blogs seek to bridge all these approaches and more by providing entries that address local place-based knowledge and situate Ethnoecology within the context of politics and history.

The ninth entry in this series is one of two contributions focused on the iconically named Salmonberry. The first group presents a brief but insightful summary of the natural and cultural history of this native wild fruit. They discuss aspects of the common property resource systems in place across much of the native Pacific Northwest by outlining the duties and obligations of certain families to the harvest and care of specific bramble patches.

The Salmonberry

NATIVE BRAMBLE IS VALUED FOR FOOD, MEDICINE, AND ROLE IN CULTURE-MAKING

Cara Moser | Gabriela Guillén | Leo Baños | Zoey Dingle

(Click on any image for a larger view.)

Kingdom: Plantae (plants)

Subkingdom: Tracheobionta (vascular plants)

Superdivision: Spermatophyta (seed plants)

Division: Magnoliophyta (flowering plants)

Class: Magnoliopsida (Dicotyledons)

Subclass: Rosidae

Order: Rosales

Family: Rosaceae (Rose Family)

Genus: Rubus L. (Blackberry)

Species: Rubus Spectabilis Purch (Salmonberry)

For centuries berries have been used for various reasons within many native tribes in the Pacific Northwest such as the Chehalis, Cowlitz, Lower Chinook, Makah, Quinault, Quileute, Swinomish (Gunther 1945) and the Iñupiat. Each berry has it’s own unique history that sometimes can be told through native legends, as seen with the salmonberry.

According to storytellers in the Chinook First Nation the coyote was “instructed to place these berries in the mouth of each salmon he caught in order to ensure continued good fishing” and for that reason this berry came to be known as the Salmonberry (Echohawk 2008).

Others say that the color of the berry resembles that of salmon egg and that is how the berry got its name. No matter what you prefer to believe you can be certain of one thing: This unique berry is very commonly known and used in it’s native range across the Pacific Northwest.

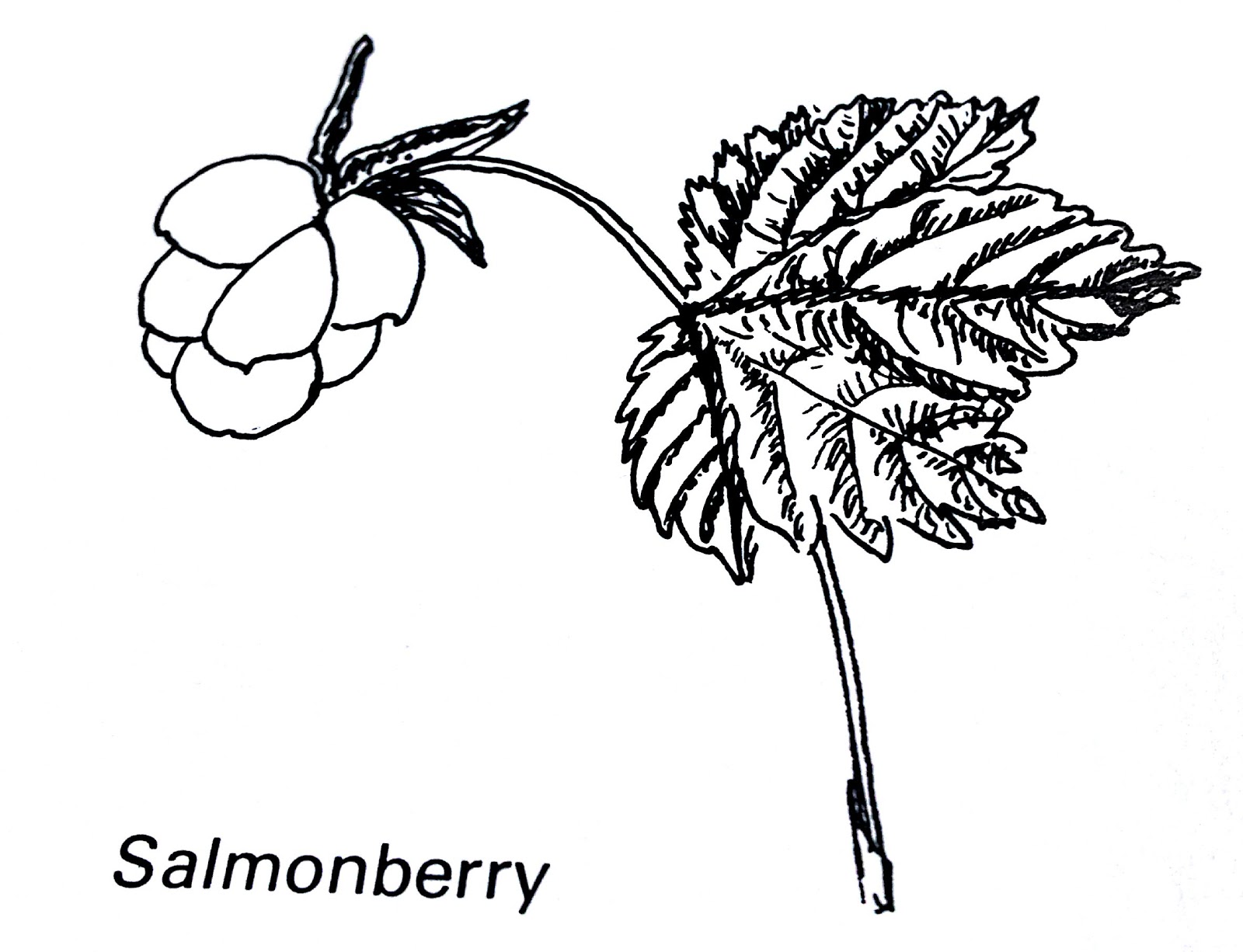

The salmonberry plant is very closely related to the blackberry and raspberry. The fruit ranges in color from a pale yellow to a deep red. Surprisingly, despite common assumptions the yellow berries have a sweeter taste than the red ones.

The salmonberry shrub is biennial, which means that only the second-year canes bear flowers and fruit. The small flowers grow scattered from top to bottom on the shrub and have five petals, giving the blossom its distinct star-shaped quality, and typically range in color from deep purple to bright magenta. In Alaska, the Iñupiat are familiar with a variety that bears a white flower.

At first glance it may be difficult to identify a salmonberry bush because of the similarities it has with both the blackberry and raspberry. There are some discernible differences to the trained eye. Here is video that can help make that identification a bit easier.

Salmonberry bush? How can you tell?

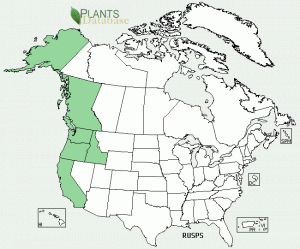

The salmonberry has a wide range and its habitat is also quite varied. It grows along the Pacific Northwest coastline, and its habitat is primarily concentrated in the wetlands and marshlands of Alaska, British Columbia, Washington, Idaho, Oregon, and northern California (see Map below).

Its ability to grow in a variety of different terrains and environments has encouraged people to develop a variety of uses depending on the time of year the wild fruit is harvested.

According to anthropologists, the salmonberry plant is a symbol of prestige among many First Nations of the Pacific Northwest.

This is a controversial claim since the concept of “prestige” is largely a Western European one and it may be more accurate to speak of the native concept of coevalness, which in this context means persons gain the respect and admiration of the community by fulfilling their ancestral obligations.

It may be that the salmonberry represents that fulfillment of that obligation for certain families and clans – this is not a universal symbol for all families and clans.

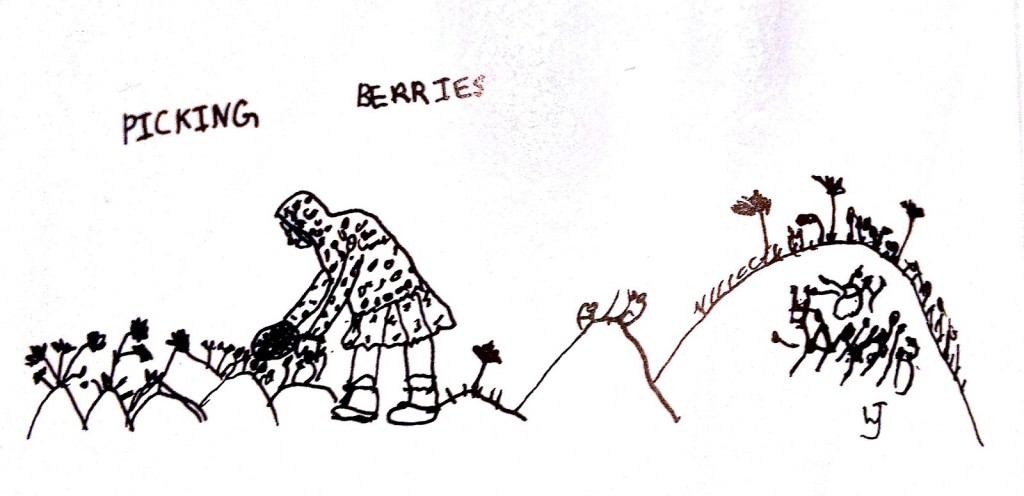

There is a gender division of labor in the Pacific Northwest native communities that has ancient roots. However, differentiation does not always lead to stratification (or hierarchy of authority and power), as Professor Peña explained to our class.

Between late summer and early autumn, when the salmonberry brambles start to bear fruit, women traditionally have been responsible for the harvest of salmonberry.

The selection and quantity of harvest requires deep ecological knowledge and respect for norms designed to protect the plant and its habitat for future generations. Quantities sufficient to store for celebrations or to serve at salmon feasts are harvested and this is why most First Nations in our bioregion have specific individuals and families with responsibilities to harvest select salmonberry patches. This is not an open-access common but instead a lineage and clan-based system of closed access to specific bramble patches.

Since the salmonberry is native to the Pacific Northwest, most of the politics surrounding this plant lie within the realms of harvesting, cultivating, and processing. Among the Coast Salish peoples, families with rights to harvest specific patches reserve the first and second rounds of picking. This initial and generally more bountiful harvest is dedicated to communal feasting, after which the privilege to forage in the patch is opened to the rest of the community.

The salmonberries are used in a variety of ways and not only food but medicinal uses as well. The bark and leaves have astringent properties and can be consumed as teas to treat diarrhea or dysentery.

In Western Washington, salmonberries are eaten fresh and often as an accompaniment to smoked salmon. They are eaten fresh because they are considered too soft to preserve in jams or jellies and too wet to be dried into cakes for winter stores.

The plant is also used for the production of material goods. For example, the Makah make tobacco pipes from salmonberry brambles. They “dry and peel a branch of salmonberry, remove the pith and use it for a pipe stem” and “the Quileute plug the hair seal float used in whaling with the hollow stem of elderberry wood, then insert a piece of salmonberry wood as a stopper,” which can be easily removed to further float the boat. (USDA 2000).

The Kaigani Haida people line baskets with the salmonberry plant, wipe fish down with the berry, and use it to cover other foods.

Today, with the introduction of pectin and refrigeration, the berries are also frozen, canned, and made into jams and jellies.

Works Cited

Bulson, Ray. “Salmonberry.” Wilderness Visions, Inc.. Web, http://www.raybulson.com/Large_Photo_Pages/photoID_20100708-Wildberry-MG_4442.html.

EchoHawk, Terry . “04.02.08–Traditional Medicine and Foods–Salmonberry and Thimbleberry « Raven’s Ruff Stuff And Other Things Native.” Raven’s Ruff Stuff And Other Things Native. http://arcticrose.wordpress.com/2008/04/02/040208-traditional-medicine-and-foods-salmonberry-and-thimbleberry/ (accessed November 18, 2012)

Flags of Lewis and Clark, “Encounter Tribes.” Last modified 07/08/2002. Accessed November 20, 2012. http://www.tmealf.com/lewisclark/lc.htm.

Gunther, Erna. “Ethnobotany of Western Washington Revised Edition 1973.” (Seattle; University of Washington, 1945), p. 35.

Harune, B. ”Native American Coyote Design.”Deviantart. Last modified 10/29/2009. Accessed November 20, 2012. http://bharune.deviantart.com/art/Native-American-Coyote-Design-85232991.

Home Bug Gardener, “For Madeline in May.” Last modified 05/14/2011. Accessed November 20, 2012. http://homebuggarden.blogspot.com/2011_05_01_archive.html.

Jones, Anore. “Nauriat Nigiñaqtuat Plants that we Eat.” (Manilaq Association, 1983): v, vii, 71-77.

Lincoln, Kelly . “Salmonberry Season – The Delta Discovery.” The Delta Discovery Homepage. http://www.deltadiscovery.com/story/2012/08/08/in-our-native-land/salmonberry-season/359.html (accessed November 19, 2012).

“Rubus Spectabilis.” Rubus Spectabilis. N.p., n.d. Web. 20 Nov. 2012. <http://www.fs.fed.us/database/feis/plants/shrub/rubspe/all.html>.

“Salmonberry Bush? How can you Tell?.” Posted 06/02/2009. United Montessori Association. 06/02/2009. Web, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3fH_6mRJN9U&feature=related.

Stevens, M., and D. Darris. “Plant Guide for Salmonberry (Rubus Spectabilis).” USDA-Natural Resources Conservation Service, Plant Materials Center, Davis, California. 2000.

________________________________________

About Devon G. Peña

A lifelong activist in the environmental justice and resilient agriculture movements, Devon G. Peña is a Professor of American Ethnic Studies, Anthropology, and Environmental Studies at the University of Washington in Seattle. He also works on the family’s historic acequia farm in San Acacio, Colorado.

A lifelong activist in the environmental justice and resilient agriculture movements, Devon G. Peña is a Professor of American Ethnic Studies, Anthropology, and Environmental Studies at the University of Washington in Seattle. He also works on the family’s historic acequia farm in San Acacio, Colorado.

A pioneering interdisciplinary research scholar and widely-cited author, his most recent books include Mexican Americans and the Environment: Tierra y Vida (U. of Arizona Press, 2005) and The Oxford Encyclopedia of Latinos and Latinas in the United States (senior editor, Oxford University Press, 2005).

Dr. Peña is the Founder and President of The Acequia Institute, the nation’s first Latina/o charitable foundation dedicated to supporting research and education for the environmental and food justice movements.

Read this article as it was originally published here.