Goats… what makes goats so fascinating? Is it their friendly inquisitiveness? Their obvious affection and sense of humor? The odd horizontal pupils in their eyes? Or is it simply the fact that they have been part of our lives for thousands of years?

As long ago as 10,000 BC, humans domesticated goats in what is now Iran. To the first agricultural people, the goat was as important as the buffalo was to the Plains Indians – a nose-to-tail supply house, a renewable provider of meat, milk, fiber, and manure. Goat hides were used to make water and wine bottles and even parchment. Goat cheese was probably one of the earliest made dairy products.

Goats are hardy animals and survive on a diet of vines, weeds, and shrubbery rather than grass like cows and sheep. They can live in dry, scrubby environments and thrive.

Goats are hardy animals and survive on a diet of vines, weeds, and shrubbery rather than grass like cows and sheep. They can live in dry, scrubby environments and thrive.

They are also the perfect size to farm and milk, especially for the increasing number of women who are principal farm operators. The 2007 Census of Agriculture (the most recent available) reports more than 300,000 women are now operating farms, up almost 30% from five years earlier.

In 2007 there were 27,500 farms in the US raising dairy goats and 335,000 goats in those operations. Compare that with the number of dairy cow operations – 9.2 million cows were raised on 65,000 farms.

Goat’s milk has some very different properties. First, goat’s milk does not contain agglutinin, a protein that makes the fat globules cluster together. In other words, it is “naturally homogenized” and cream doesn’t automatically rise to the top like cow’s milk.

The milk protein forms an easily digested soft curd and there are only trace amounts of casein protein present, which can cause allergic reactions. Children – and adults – who are lactose intolerant can often handle goat’s milk better than cow’s milk.

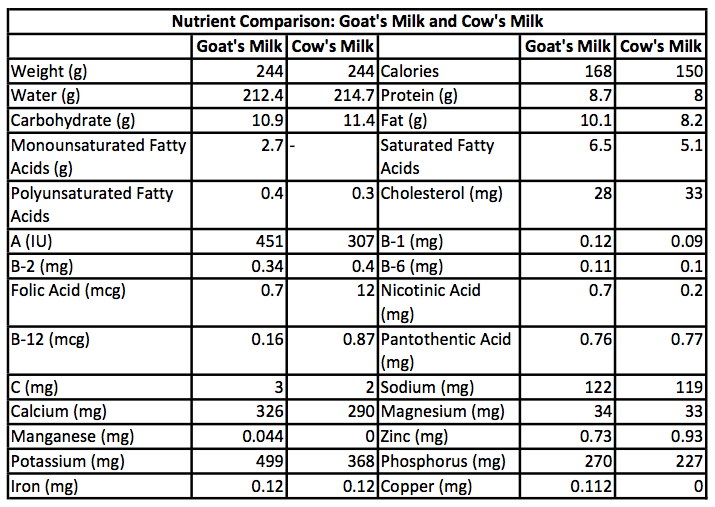

And finally, goat’s milk has approximately the mineral content of cow’s milk and yet is higher in calcium and a wide range of vitamins.

Goat Cheese Renaissance

In recent years we have seen a resurgence of small-scale and farmhouse cheese makers. Beginning in the 60s and 70s, the “Back to Nature” movement was the impetus, and by the late 70s and early 80s more specialty cheese making operations flourished.

Today there are hundreds of small-scale specialty and artisanal cheese factories in nearly every state producing local and regional cheeses out of all types of milk in limited quantities. Some are farmstead productions, which means that the cheese is made on the farms where at least 50% of the milk is produced. Goat cheese is a small but growing niche in the cheese world.

However it takes a lot of goats to produce any volume of cheese. Goats give an average of 1,800 to 2,400 pounds of milk during the animal’s lactation period; while cows average 15,000 to 37,500 pounds of milk over a similar period. It takes 8 to 10 pounds of cow or goat milk to produce a pound of cheese.

Silvo-Pasturing and Timber Management

On Sunny Pine Farm, a small farm tucked in a Ponderosa pine forest outside of Twisp, Washington, Ed and Vicky Welch and their cheeseman Mark Skatrud make fresh cheese – chèvre and feta – and yogurt from a herd of about 55 milk goats in a top-of-the-line commercial cheese operation. Holder of Washington organic certification #14, awarded in 1988, Sunny Pine is one of the original organic farms in the state.

On Sunny Pine Farm, a small farm tucked in a Ponderosa pine forest outside of Twisp, Washington, Ed and Vicky Welch and their cheeseman Mark Skatrud make fresh cheese – chèvre and feta – and yogurt from a herd of about 55 milk goats in a top-of-the-line commercial cheese operation. Holder of Washington organic certification #14, awarded in 1988, Sunny Pine is one of the original organic farms in the state.

(Take a tour of Sunny Pine Farm here.)

A farm in a western pine forest provides special opportunities for both grazing and timber management. Ed is an Oregon State University-trained forester and he carefully manages his woodlot for fiber production, pastures for rotational grazing, and fire safety.

In the past, Ponderosa pine forests, which are naturally fire-resilient, burned once every seven to ten years, clearing out undergrowth to leave an open understory with a grassy forest floor. Without fire – thank you, Smokey the Bear – brush grows up under the trees and the occasional fire that does occur burns hotter, destroying the forest – and nearby buildings.

By pasturing the goats in the woodlot in the spring, the forest is kept in a more natural state. Goats are grazed only in the spring, because that’s the only time grass is growing in this dry country. Once summer arrives and the rains stop, the goats are pastured on open fields and fed hay grown on property the Welchs own or lease.

It is this silvo-pasturing and forest management that has made it possible to selectively harvest the timber on the farm 3 times over the last 30 years, improving the health of the stand and quality of the lumber and reducing the risk of crown fires. All the barns and farm buildings have been built with wood harvested on the property and milled on site. Another example of silvo-pasturing in practice is Pine Stump Farm in Omak WA, just 40 miles to the east.

From New Zealand to Twisp, Washington

Trained in New Zealand with one of the top chèvre makers there, Mark added his animal husbandry skills to Sunny Pine to double the milk production over the last year with the same number of goats and completely revamp the cheese making.

Trained in New Zealand with one of the top chèvre makers there, Mark added his animal husbandry skills to Sunny Pine to double the milk production over the last year with the same number of goats and completely revamp the cheese making.

Sunny Pine’s goats start giving birth in mid-March and give milk until the middle of November. All the animals go through lactation together so the milk changes throughout the year. At the beginning of the season the goats produce the highest volume with the highest amount of butterfat and protein solids. As the season progresses, dry conditions cause the butterfat and protein to decrease. The ratio of fat and protein to liquid rises again in the fall as the milk volume decreases.

In the summer, the goats are rotated from pasture to pasture during the day and fed hay at night. Feeding on a good quality pasture means more milk; a poor quality pasture results in less milk. In the Methow Valley (north central Washington) it takes about an acre of land to maintain each goat because it is so dry in the summer and the pastures are snow covered in the winter.

In the summer, the goats are rotated from pasture to pasture during the day and fed hay at night. Feeding on a good quality pasture means more milk; a poor quality pasture results in less milk. In the Methow Valley (north central Washington) it takes about an acre of land to maintain each goat because it is so dry in the summer and the pastures are snow covered in the winter.

From down under, Mark brought a new milking regime: milk once a day rather than twice. For most North American dairymen that thought is totally incomprehensible, and yet it works. Milking 2 times a day, morning and night, does not result in twice the milk as a single milking.

Here is how Mark pencils it out, “Going to once-a-day milking, you will lose about 20-25% of your production, with half the labor and other handling costs. And, most important, it makes dairying more farmer friendly.”

It has become increasingly difficult to convince young farmers to move into artisan dairy operations when they have to milk twice a day for 7 days a week and then make cheese every day. Milking once a day means that they are done by lunchtime, allowing the afternoon for other farm chores and a “real life.”

Sunny Pine Organic Chèvre, Feta, and Yogurt

While Sunny Pine’s cheeses are handcrafted farmstead cheeses, they are produced in a 21st century milking parlor and cheese factory where food safety and cleanliness are top priorities and a detailed HACCP plan is in place.

HACCP (Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points) is a management system to “insure food safety through the analysis and control of biological, chemical, and physical hazards from raw material production, procurement and handling, to manufacturing, distribution and consumption of the finished product.”

No one is allowed in the cheese plant except the cheese maker and he must shower and put on fresh clothes before entering to prevent sloppy practices that can cause health and safety problems. “We are not trying to be big,” says Mark. “We are professionals, not a ‘fly-by-night’ operation that people fear is a trouble maker.”

No one is allowed in the cheese plant except the cheese maker and he must shower and put on fresh clothes before entering to prevent sloppy practices that can cause health and safety problems. “We are not trying to be big,” says Mark. “We are professionals, not a ‘fly-by-night’ operation that people fear is a trouble maker.”

Three flavors of chèvre are in production: garlic and black pepper, parsley and chives, and a very special honey and lavender, made with an infusion of lavender grown on the farm. All are made from vat-pasteurized milk – no fresh cheese can be made from raw milk. The chèvres are packaged in 6-ounce tubs and vacuum-sealed for a 6-week shelf life.

Where to Buy?

Sunny Pine cheeses are available in small regional natural food co-ops like the Skagit Valley Food Co-op in Mount Vernon, the Central Co-op’s Madison Market in Seattle, local stores and restaurants throughout the Methow Valley, and the Twisp Farmers Market in the summer.

Good news! These lovely cheeses and yogurt will soon be available throughout Puget Sound in larger markets.

We’ll keep you posted!

For more information visit: Sunny Pine Farms

ADVERTISEMENT

[column grid=”3″ span=”1″]

From Skipstone Books

City Goats: The Goat Justice League’s Guide to Urban Goat Keeping is a book for gardeners, people committed to eating locally, and anyone who has ever pondered joining the backyard goat revolution.[/column][column grid=”3″ span=”1″]

City Goats: The Goat Justice League’s Guide to Urban Goat Keeping is a book for gardeners, people committed to eating locally, and anyone who has ever pondered joining the backyard goat revolution.[/column][column grid=”3″ span=”1″]

From Skipstone Books

In Food Grown in Your Own Backyard, Colin McCrate and Brad Halm teach beginner growers from all walks of life the techniques of organic food production. [/column][column grid=”3″ span=”1″]

In Food Grown in Your Own Backyard, Colin McCrate and Brad Halm teach beginner growers from all walks of life the techniques of organic food production. [/column][column grid=”3″ span=”1″]

From Skipstone Books

Annette Cottrell and Joshua McNichols turned their love of whole, minimally processed, naturally grown food into both a passion and a book: Urban Farm Handbook.[/column]

Annette Cottrell and Joshua McNichols turned their love of whole, minimally processed, naturally grown food into both a passion and a book: Urban Farm Handbook.[/column]

Good to know I taught Mark something “down under”

You did a great job teaching him! Sunny Pine is a beautiful example of technology, talent, and art!

Gail NK

Co-Editor/Publisher

GoodFood World