Farm to Table – Who Chooses?

We’re all busy people, and we can easily be overwhelmed by the bewildering array of products on the supermarket shelves. According to the FMI (Food Marketing Institute), the average supermarket today carries nearly 39,000 items.

How those products make it to the shelf is something that most of us don’t know. Why is this product available and not another one? Who determines what it is that you get to buy? As you stand in the produce section of the grocery store, and reach out to select a piece of fruit, you are deciding what you get to eat, right?

Well, actually you don’t! Yes, you get to decide which item you’ll take off the shelf, but how did it get there? That decision is made by lots of folks in the supply chain and only incidentally by the consumer.

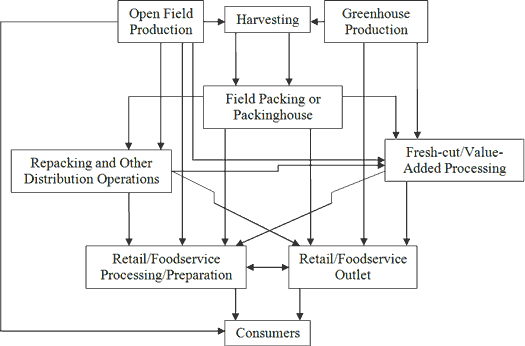

The “Food Supply Chain” is, in reality, many supply chains. Each group of products – meat, dairy, produce, grocery items – move through a different system, and each of those systems is unique. This week we start with the produce supply chain and will take a look at the others over the next several weeks.

There are a lot of steps between the farm and the table, and this is a fairly general overview!

The Farmer Chooses What He or She Grows

You thought the farmer got to choose what he or she grows? Actually that’s not as simple as it sounds. If your farm sells direct to you, through the farmer’s market or a CSA (Community Supported Agriculture) arrangement, they have most likely based the crops they grow on what best sells – what you buy. In Puget Sound, for example, small farmers grow most of the produce that is sold direct to consumers. So you do get to choose by “voting with your dollars.” If a particular crop doesn’t sell this season, your farmer just won’t plant it next year.

A medium-sized farm is likely to sell through an aggregator who merges his or her produce with similar products grown by other farms in order to create volumes enough to sell into a regional or national distribution network.

It begins to get complicated here because individual retailers like small co-ops and individual markets will buy direct from farmers while small chains will likely buy from a local or regional distributor who buys direct from the farmer. Ah, starting to sound like the “House That Jack Built,” eh?

Because there is now a middleman between the consumer and the farmer – actually, two of them: the retailer and the distributor – the farmer no longer grows what the consumer asks for, but grows according to the direction of the retailer and/or distributor. Distributors, for example, prefer tomatoes to be hardy, easy to handle, and travel well; taste has nothing to do with it.

That may limit him or her, for example, to only a select limited number of varieties of apples or tomatoes, not the particular heritage variety you prefer.

The Government Chooses What the Farmer Grows

Large farms and agribusinesses – Big Ag – are considerably influenced by government subsidies and purchasing programs. Depending on location, large farms are likely to grow corn or soybeans for grain or fuel rather than for food because of the huge subsidies available.

At the same time, government purchasing programs like school lunch programs can drive the production of certain food items like potatoes.

Food Manufacturers Choose What the Farmer Grows

Big Food – represented by companies such as Kraft, Campbell’s, General Mills, or McDonalds – have a huge influence on what type of crops are grown. McDonalds is the single largest purchaser of beef, pork, potatoes, and apples in the US; you can bet that if McDonalds wants a certain kind of potato that’s what the farmer will grow. It’s the Russet Burbank, by the way. There are also special varieties of potatoes grown for making potato chips. Thank you, Frito Lay, for making the choice for us.

Food Manufacturers Choose What You Get to Buy

Foods that are processed and sold in packages are several steps removed from the farm. In order to process and prepare $7.8 billion dollars worth of food products, Campbell’s buys millions of pounds of fruits and vegetables. The wholesalers they buy from contract for specific varieties at specific quantities.

If a particular fruit or vegetable does not “perform well” in the manufacturing process, it simply is not purchased. No buyer for a variety, no variety grown; end of story. For your information, Campbell’s uses a “Jersey” variety that produces a deep-red, fleshy, Roma-shaped tomato. By the billions…

Large packaged food manufactures also insure that you see their products on the shelves by paying a “slotting fee” to large supermarket chains for the right to the space. Common practice in the food business today, this kind of “pay for play” arrangement (Payola) was outlawed in the music industry in the 60s.

And, there on the shelf, are your “favorite” tomato soups!

Your Retailer Chooses What You Get to Buy

Much like a food distributor, a retailer must look at the preference bell curve. If a product doesn’t fit the appetites or taste buds of a majority of shoppers, it isn’t likely to get past the particular category buyer.

A produce buyer is charged with keeping the appropriate volumes of the best selling varieties in the store at all times. That may mean buying tomatoes from California in July when local tomatoes are ripening around you. Or buying blueberries from Chile in February when the competitor across the street is carrying them.

Do You Really Get to Choose What You Buy?

Clearly the products on the supermarket shelves have been filtered through a variety of levels before you stand in front of them making your purchasing decisions. Do you really get to choose what you buy? Unfortunately, you only get to choose from a carefully prepared, packaged, and marketed selection.

Shorten the link between the farm and the fork; buy direct from a grower, butcher, baker, or cheese maker if possible. If not, buy from a food co-op or small market and work as a partner to insure that a wider variety of fresher products are available and support the community around your food choices.

There’s More Coming

As a consumer, you have very little control over the products that appear on the grocery shelves. You are like a contestant playing the “Dating Game;” you get to choose from a predefined assortment of products.

This week, we looked at the produce supply chain, and ways to shorten it. In the coming weeks, we will look at the meat, dairy, and grocery supply chains. All of them are complex and yet as you understand them, you can take more control of your food sources and make better food choices.