Intuitively, the benefit of spending food dollars locally is fairly obvious – right? More dollars circulating locally means greater support to local businesses for a healthier community economy.

Simple enough, but in explaining the local multiplier to local food advocates and policy-makers, things can get complicated fast. That’s why I hope this piece might inform a broader discussion on how we want our local economy to grow.

Let’s begin with the local multiplier itself. Local multipliers are economists’ way of measuring the economic power of locally directed spending. Food dollars flow in and out of a community through many different channels, such as import and export sales, tourism, taxes and tax benefits.

But in the time between dollars entering and leaving the community is the possibility of circulating those dollars within the community, that is, increasing the number of economic transactions taking place inside the community. The significance of slowing down the throughput of dollars is that each time a dollar is spent – or re-spent – the income to the community goes up by a dollar. Multipliers express how much additional spending occurs as a multiple of the original spending – hence the term “multiplier”.

Now, higher local dollar flows also represent an increase in the productive activity of the community. After all, those dollars are being exchanged for something. In this sense, local multipliers reflect the economic opportunities within the community. If no one is growing food locally, your food dollars are going to leave the community. But it can also be the case that there are local producers and (obviously) local consumers but nothing that connects the two.

That connection usually happens in the marketplace – in the case of food, both literally and figuratively. The direct sales revolution – the rise of CSA’s and farmer markets – vastly increased the opportunities to buy locally as well as sell locally. The point here is that the more linkages there are between buyers and sellers within the community and the stronger they are, the higher the local multipliers and the healthier the community’s economy. So, in addition to quantifying dollar flows, local multipliers also indicate the number and strength of linkages in the local economy. In turn, these linkages represent choices about where to buy but also where to sell, and, by extension, who to buy from and sell to.

This then is what is behind the local multiplier – choices about whom to trade with. But it’s important not to fall into the trap that it’s all about individual choice as these choices are often structured by things beyond the control of individual consumers and businesses.

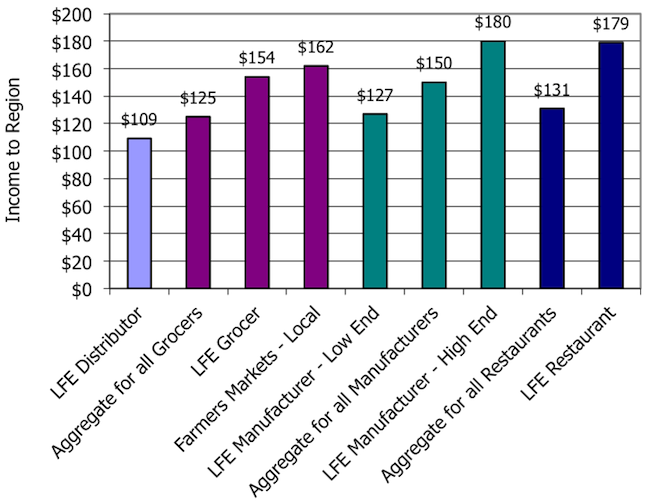

This is the message underlying findings from the local multiplier study I reported on here. The chart below shows the impact of $100 in locally directed spending (one way to represent the multiplier) for different categories of businesses. The category of business with the lowest multiplier is local distributors and that with the highest is local manufacturers high end with local restaurants a close second.

(In the chart, “LFE” stands for local food economy, a designator which distinguishes locally owned businesses from all businesses with operations in a given area, that is, including businesses headquartered outside of the region designated local.)

In general, we see that local businesses in a category have higher local multipliers than all businesses in that category. However, with manufacturers some local manufacturers – LFE manufacturers – have lower multipliers than all manufacturers.

What explains that? It turns out that some manufacturers must logically source materials form outside their region, such as the case with many bakeries who are not located in grain growing regions of the country.

The flip side of this pattern is that many manufacturers locate close to their product input sources. So you might have a processor which sources locally but ends up exporting most of its product, that is, it chooses to export most of its product. Or perhaps I should say they have to export because of the way the markets they operate in are set up.

In fact, the biggest constraint on where businesses choose to sell is the size of their operations. Consider the mid-sized farm whose output is too great to sell through farmers markets and too small that they can set their own prices with distributors. That is why distributors have such low multipliers – they have to move a large volume on small margins to make profits.

Local multipliers help reveal what choices consumers and businesses have now but they also tell us what we can do to increase our choice about what kind of economy and food system we want to have. Consumers can understand how their individual choices make a difference to the growth of the local food system and businesses can gain insights into what social and physical infrastructure needs to be put in place to broaden their choices. This is what I think make multipliers interesting in the end.

And while many choices on where to buy or sell are beyond the control of individual consumers and businesses, we all can choose to act together to change the options.

Viki,

I feel like this article is SO IMPORTANT, and yet, I am trying to grasp its implications and advice, in my own life. I see far too little local produce offered at my local Whole Foods – I often think how crazy it is that the “local” NY State apples aren’t as readily available as I’d prefer(for instance) , they come from Massachusetts instead. And I bet Massachusetts is receiving OUR asparagus, or cranberries and peaches??

I’m also dismayed at how expensive the local farmer’s market is… crowded, fun perhaps, an outing for sure, but not less expensive than whole foods. I would like more information on HOW to better determine

not only who to buy from, but who and how to increase the cross connections within one’s home state that you speak of.

I went to look at your local multiplier….and glazed over seeing 160 pages!

I think this is really important, personally confusing, and I wonder if we can speak together on this. Perhaps we might help others…you with your reporting/understanding of the policies/politics and directed political action – me with hands on…what /when/ how recommendations of our food purchases.

A related pet peeve of mine is that I HATE seeing when Whole Foods seemingly buy out another product I love… and they snatch it up under the “365” label. Help me understand if my anger is warranted, because I am a loyal product purchaser and feel the huge corporation shouldn’t be buying up the small producer.

Thank you for your articles.

Ina D.