On March 1, 1936, President Theodore Roosevelt signed the Soil Conservation and Domestic Allotment Act, one of the earliest pieces of agriculture legislation. The law had three major objectives:

On March 1, 1936, President Theodore Roosevelt signed the Soil Conservation and Domestic Allotment Act, one of the earliest pieces of agriculture legislation. The law had three major objectives:

- Conservation of the soil itself through wise and proper land use.

- Reestablishment and maintenance of farm income at fair levels

- Protection of consumers by assuring adequate supplies of food and fiber

Seventy-five years later we are still working on legislation that purports to have the same purposes.

Dan Imhoff, author of Food Fight – The Citizen’s Guide to a Food and Farm Bill, was in Seattle to bring attention to the debate just beginning over the upcoming legislation. He spoke at the University of Washington on March 1 and following is a summary of his comments.

For the first time in the history of the Farm Bill, consumers are becoming a force to contend with. And the 2012 Farm Bill is drawing more attention than ever from both politicians and consumers.

In the past, the Farm bill was a game for two major forces: the hunger/nutrition camp interested in getting food benefits to Americans who are poor or unemployed and the commodity groups representing farmers that raise a narrow selection of “storable” crops. Five of those crops – wheat, corn, soybeans, rice, and cotton – get 90% of the subsidies distributed. And only two of them are grow as food crops (wheat and rice); a very small percentage of the corn and soybeans are actually consumed directly, most goes to feed livestock. One third the corn crop is going into biofuel.

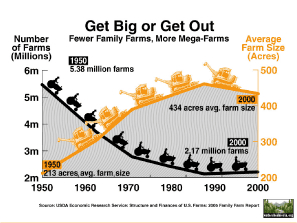

American agriculture has become increasingly concentrated and industrialized. In the 1950s we had 6 million farmers growing our food, we are down to 300,000 producers who generate 90% of the agriculture output. They’ve become very successful at making meat and commodities – those storable crops – abundant and cheap. They are also producing crops that are linked to diets high in salt, fat, sugars, and processed food.

American agriculture has become increasingly concentrated and industrialized. In the 1950s we had 6 million farmers growing our food, we are down to 300,000 producers who generate 90% of the agriculture output. They’ve become very successful at making meat and commodities – those storable crops – abundant and cheap. They are also producing crops that are linked to diets high in salt, fat, sugars, and processed food.

Imhoff believes that agriculture is a public good, that our farmers need to be supported and kept on the land. We spend only 2 1/2% of our total Federal budget on agriculture; and while we don’t spend enough, we also don’t require enough from those we do support.

Subsidies in the form of direct payments to farmers total about $5 billion a year, and yet those subsidies have become “disconnected” from soil protection, soil improvement and water quality. For example, in the 2008 Farm Bill there was reform in the crop insurance program. The government insures your production, regardless of where the crop is planted. If you look at a make of farming operations that have received disaster support over the last 10 or 20 years, you’ll see farms that get assistance every couple of years. We have created a protected agriculture base that is farming in places where they shouldn’t be farming.

When grain prices or ethanol subsidies go up, farmers plant more on marginal land. If the experiment doesn’t pan out, hes insured for the experiment.

We should also subsidize alternative agriculture and grazing programs; organics have been underfunded by Farm Bill subsidies for the last 20 years.

What many Americans don’t know is that the “Farm Bill” is really a “Food and Farm Bill:” nearly 70% of the funding from the bill supports nutrition programs for the more than 40 million Americans who are “food insecure.” The real question is whether the Farm Bill is a good vehicle for delivering food support to low income people.

It’s our money that is being spent and this is an opportunity to invest in a new food system. The current system not only funds 60% of the USDA budget with the Farm Bill, the USDA is also charged with giving nutritional recommendations to consumers. On the one hand, the bill funds the growth of 10 heavily protected subsidized crops that are the basis for a diet heavy in processed foods, while on the other hand, the USDA recommends that we move away from those foods and eat fewer animal products.

There is a heightened urgency about the sources of our food. A new food movement is trying to link health to the industrialization of agriculture. This movement is trying to bring more diversity, healthier, more regional food to our diets.

It is a food citizen movement that wants our food to be healthy, to have a free market and good food in our schools, environmental support and job creation, through a healthy food and agriculture system.

More Information

For those who wish to learn more about crop subsidies, Mark Bittman, New York Times columnist, detailed the issue in Further Reading on Agricultural Subsidies.

For more about Dan Imhoff, his books, and his publishing company – Watershed Media – click here.