In The Right Price for Good Food – Part 1, I proposed that the right price for good food depends on whom you’re asking, which may possibly explain why discussions around food prices are so lively. It’s almost gotten to the point that we have a tug of war going on between food producers and consumers around what should dictate price, especially now that prices are rising. Today, I address the issue from the farmer’s perspective.

Most people who care about good food are at least somewhat aware that the (mostly small) farms which grow good food scrape by financially while farm bill subsidies go to large commodity farms. How these subsidies shape market prices and in turn our product choices is what I will explore in this second of three pieces on food prices.

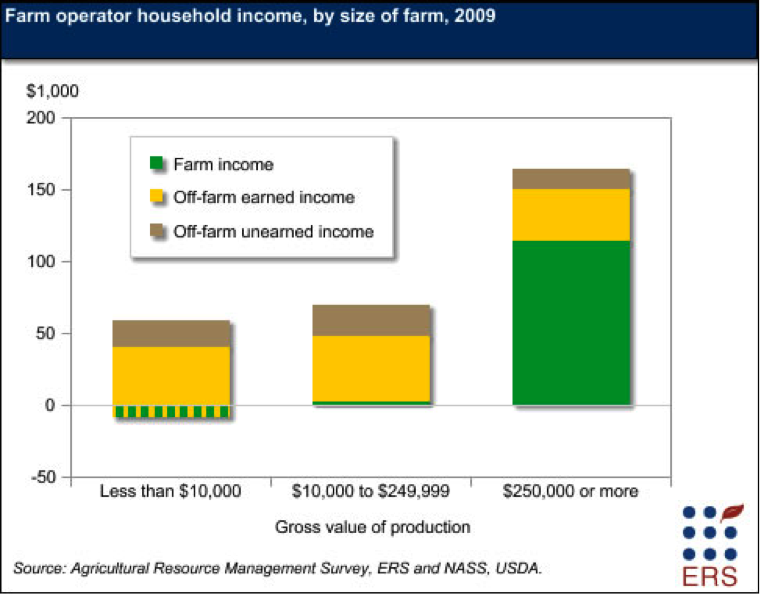

The chart below shows average incomes by income source for different classes of farms based on their gross value of production. While these are national averages, the income distribution pattern holds for most regions in the U.S., including here in the Northwest.

On one side of the scale, commodity farms that yield $250,000 or more of products average more than $100 thousand in farm-related income including subsidies. These farms make up about 10% of all family farms.

The majority of what we might call “good food farmers” fall into the $10 to $250 thousand dollar bracket in the chart. As seen from the chart, these farmers average less than $5000 a year in farm income – what’s left over after paying the costs of land, inputs and labor. Moreover, the income they make from holding down off-the-farm jobs is nearly ten times what they make from farming.

Farmers who produce less than $10 thousand worth of food per year (60% of all family farms) make even less in farm income. In fact, these farmers effectively subsidize the operation of their farms with off-farm jobs. That’s right – they may be paying you to eat the food they grow or raise. (They might also be hobby farmers willing to settle for a tax write-off.)

It should be clear from the above data that whatever the price we are paying for good food, the farmers who grow it are not getting rich off it. This is not to say that good food, locally grown, does not command a “premium.” In fact, there is an increasing amount of local evidence to suggest that selling to local food markets is a lot more economically viable than selling to commodity markets for the majority of farmers – the 90% with less than $250 thousand in annual sales.

For example, in 2007, King County vegetable farmers made 12 times the dollars per acre (excluding subsidies) than did farmers in Snohomish, one county to the north. One explanation for this dollar differential is that King County farmers sell almost exclusively to the local market in Seattle whereas Snohomish County farmers sell more than half their output to processors. Put another way, King County farmers use direct sales to control price (reflecting more closely their actual costs) while Snohomish County farmers are price takers.

But should paying extra (on top of commodity prices) really be considered a premium? Prices need to be linked to the costs of production including fair wages for farmworkers. Good food farmers are not only tasked with providing our food but with caretaking the land and surviving and competing. Part of what affects price is the risk involved in farming operations and as rising global food prices demonstrate, farming is a particularly risky business in the age of global warming. Competing means spending many hours doing direct sales – connecting to the communities they live in. Good food farmers and the people who work for them should be paid for this good effort.

From the farmer’s perspective, I think we can conclude that market prices are insufficient. To be fair, prices should pay for the costs and work of sustainably producing fresh, healthy food. That won’t happen as long as we are subsidizing industrial farmers to grow cheap food. What will change this is when good food farmers no longer are competing with commodity producers and their subsidies.

Watch for the next in this series: The Right Price for Good Food – Part 3: From the Consumer’s Perspective.