Amanda Irving and René Featherstone are an unlikely partnership and yet it takes both – the farmer and the baker – to turn an ancient grain like spelt into delicious bread.

Bread is one of the oldest processed foods and yet it is one of the simplest.

As early as 30,000 years ago, ancient humans made a kind of flatbread by baking the starch from pounded roots on stones, but it wasn’t until the spread of agriculture around 10,000 BC that grains were used for making bread.

About 8,000 years ago that the kind of wheat we use for bread making, Triticum aestivum, was discovered. It was the first wheat where the husks would “shatter” and the grain fall free without milling.

Grains of spelt, emmer, and einkorn have strong husks that enclose the grain and must be removed by threshing or pounding. Spelt is thought to be a hybrid of “bread wheat (T. Aestivum)” and emmer.

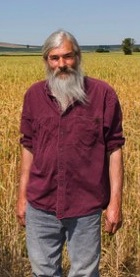

Spelt, emmer, and einkorn – “farro” or “hulled” grains – are grown in eastern Washington on Lentz Farms by René Featherstone and Lena Lentz Hardt. Established in 1898, Lentz Farms grew wheat and barley for more than 100 years. And like most farms raising wheat, Lena and René were challenged with wheat prices that rose and fell on the commodities markets.

In the late 1990s, they decided to experiment with ancient grains and René requested seed from the USDA National Small Grains Collection (NSGS) in Aberdeen ID. The NSGS freely shares a wide variety of small grains; however those small grains come in very small packets! René received 1 gram of spelt, 1 gram of emmer, and 1 gram of einkorn to grow. One gram is 5-10 kernels!

By planting and replanting, removing rogue plants, and fighting off hungry birds – during one growing season, a flock of song birds ate 90% of his einkorn crop in a single day – René was able to finally grow enough grain to harvest one small field mechanically. It took him 8 years to do it!

Today – 12 years later – Lentz Farms sells 90% of the spelt they raise to Bob’s Red Mill, Milwaukie OR. Small artisan bakers like Amanda’s Tall Grass Bakery or specialty retailers like Chefshop.com also buy small quantities of spelt and emmer from René and Lena.

Amanda takes the flour from those ancient grains and combines it with water, salt, and a slightly fermented “starter” to make nutritious and delicious breads.

Beginning in the late 19th century, the food processing industry caused grain farmers to focus on crops most easily refined. Bread” wheat slowly pushed the ancient grains off the farms as it was easier to harvest, and the process of bleaching the milled flour resulted in a whiter, lighter loaf of bread preferred by American consumers.

Still, making bread takes time; even with commercial yeast, the time to prepare and bake bread is measured in hours. In 1961, a “no time” method of making bread that used low-protein wheat, solid fats, chemical oxidants, large doses of yeast, and high-speed mixers cut the production time by more than half. The resulting bread needed to be fortified with a variety of vitamins and minerals to replace nutrients destroyed in the manufacturing process.

Bakers like Amanda Irving and her team of twelve at Tall Grass Bakery, Seattle WA, are bringing back healthy and nutritious breads; breads that don’t require “fortification” to provide the healthy nutrition that is missing from commercially manufactured bread.

A professional baker for nearly 20 years, Amanda learned baking from her mother, who also baked whole grain bread. While still in high school, she started her baking career and went on to get professional training at culinary school. When she graduated, Amanda came to work at Tall Grass Bakery and eight years later she bought the company.

(Take a tour of Tall Grass Bakery here.)

Today, at Tall Grass, Amanda makes primarily naturally leavened breads using a living culture of flour, water and natural yeast that many people would refer to as “sourdough starter” but she calls “levain” – French for “leaven” or “to rise”

Why do we think of bread and wine as natural partners? It’s the yeast! While most of us think of beer or wine when we hear the word “fermented,” bread is also a fermented food. The action of fermentation does two things for bread: it creates gasses that are caught in the gluten causing the bread to rise and it adds flavor.

By keeping three starters – one spelt, one whole wheat, and one rye – alive and well-fed, the Tall Grass bakers have the natural leavening needed to make a wide variety of hand-formed loaves, from baguettes (long and skinny) to boules (round).

Baking with whole grains rather than bleached white all-purpose flour requires slightly different methods of baking. “It takes more time. With whole grains, you have to soak and hydrate them a little more to get them to act in the same way as white flour,” says Amanda. “We do a lot of overnight soaks. For our hominy bread, the corn gets soaked over night and we have a bread made with steel cut oats. The oats are soaked overnight before we add them to the dough.”

For thousands of years, bread has been the “staff of life.” Fourteenth century peasants ate 2 to 3 pounds a day and the French Revolution may have begun over the price of bread. Now most bread is over processed and relegated to being a source of “fiber” in our diets; that is, when we’re not avoiding carbohydrates entirely.

American consumers have strayed a long way from real food and real bread. René and Amanda are on the path that farmers and bakers have followed for millennia: growing good grain and making good bread.

Long may that partnership last!

Photo of René Featherstone: Sound Bites Sauce & Spread Co.

He is, indeed! It’s amazing to learn that it is possible to bring a grain to market from 5 or 10 kernels! What skill and patience.

Keep reading and keep the conversation going!

Gail N-K

Co-Publisher

GoodFood World

Great article! Rene is definitely an icon in the ancient grains business. I cannot say enough good about him.