For those who are trying to farm in the Palouse region of eastern Washington, northern Idaho, and northwestern Montana, there is only one name for it – Dryland Farming. Annual rainfall levels of 8 to 16 inches mean that farmers have to be good – very good – at moisture management.

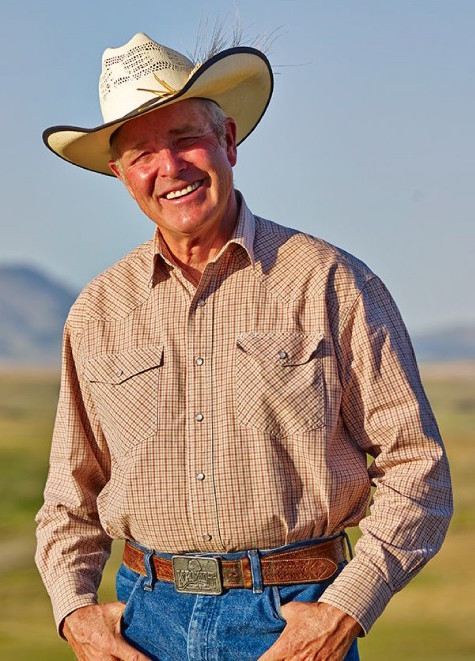

Meet Your Montana Farmer

Here are just a few of the folks who grow and process grain, pulses, peas, and chickpeas on nothing more than the moisture that falls out of the sky.

Bob Quinn, Bob Quinn, Organic Farmer, and founder of Kamut International, says: “I feed the soil, not the plant.” He farms along the “Hi-Line” in north-central Montana, just out of Big Sandy. It’s a part of the world that is cold – down to -40° in the winter – and dry, where the rain falls mostly in May and June.

Quinn’s 3,600 acres are certified organic, and it is organic farming that makes dryland farming successful. Organic rotation focuses on cover crops and green manures that are crucial to moisture retention, soil fertility, and weed management.

A multi-year rotation supports Bob’s organic farming principles:

- Soil building – growing his own fertility inputs: green manure substitutes for chemical fertilization.

- Diversification – mimicking nature by using crop rotation to break disease, weed, and pest cycles, substituting for herbicides and pesticides.

He alternates spring and fall crops, broad- with narrow-leafed plants, late with early maturing crops, heavy with light feeders, and cash crops with green manures.

These dryland farming methods have made it possible for Quinn to build a highly successful marketing company that sells KAMUT® brand khorasan wheat around the world. Mentoring other young farmers is also part of Bob’s farming principles and he has been a strong influence on many.

Young Farmers: the Bob Quinn Connection

Casey Bailey raises organic KAMUT, winter wheat, and hull-less barley on his 1600 acres that lie alongside 3000 acres belonging to his father. He is slowly converting these rolling hills outside of Fort Benton MT to organic crops.

Armed with two college degrees, Casey mixes new ideas with traditions, high tech with low tech. For example, he harvests his crops with a combine that has an on-board GPS. It is possible to capture the data as he plows an exact north/south transect at the beginning of the season, and then, when it’s harvest time, that data is used to drive the combine with no input from a operator. At the same time, special sensors weigh the grain as its harvested and continually check the moisture in the seed.

(Take a virtual tour of Casey’s farm here.)

Jacob Cowgill, Prairie Heritage Farm, Power MT, who was at one time one of Bob Quinn’s assistants, also grows a variety of grains and legumes in an organic rotation. Jacob has farmed on his own for only a few years, yet he is continually using Quinn’s methods to experiment with a wide diversity of crops.

Community support for farmers and fishermen has continued to grow through various types of “CSA – Community Supported Agriculture” (or “CSF – Community Supported Fishery) agreements. It’s not often that one finds a grain and seed CSA, but the Cowgills have been successful with their model.

In an average tear, members of the grain and seed CSA receive about 85 pounds of grain:

- 10 pounds of Crimson lentils

- 10 pounds of Red Chief lentils

- 20 pounds of Sonora spring wheat

- 15 pounds of Khorasan wheat

- 15 pounds of Lucile emmer

- 15 pound of Bronze barley

- 2 pounds of milk thistle

(Take a virtual tour of Jacob’s farm here.)

Farming in the Drylands

Daryl Lasilla and his wife, Linda, own Daryl Lasilla Organic Farms just outside Great Falls MT on about 1000 acres. Linda Lasilla is well known around Great Falls for her lentil chocolate cake!

The soil here is rich, black, and heavy with clay and the topsoil is nearly 100 feet deep in places. Daryl raises organic buckwheat, winter wheat and spelt. His spelt crop is generally so successful – chest high under extremely difficult conditions – that neighbors farming conventionally ask for Daryl’s advice.

Some years are just not good for buckwheat! A not-so-typical year can start off with a long cool wet spring that delays planting and germination. Then once the seeds are in the ground, the rain simply stops and no more falls for the next three months.

Under the best circumstances the growing season ranges from 100 to 120 days – just enough to get a crop in if the weather cooperates.

While organic grain crops may not be as successful as conventional crops during the good years, they nearly match production during average years, and exceed production during the poor years.

(Take a virtual tour of Daryl’s farm here.)

More than 100 miles to the east in Lewistown MT, Ole Norgaard, North Frontier Farms, faced the same weather challenges in a part of the state that has very thin, alkali soil.

In a year with a cool wet spring and summer drought, his corn comes to a halt. Plants that would have borne 10- or 12-inch cobs full of jet-black kernels in a good year, produce nubbins no more than 5 or 6 inches long.

Norgaard has built a portable bagging, packing, and shipping operation on his farm and is marketing North Frontier Farms Heritage Black Corn. His black cornbread mix produces a cornbread that is almost like cake in its texture and taste.

(Take a virtual tour of Ole’s farm here.)

The Network Expands

Organic grain farmers are a closely connected lot, and Jacob, Daryl, and Ole are linked through Timeless Seeds, Ulm MT. Since 1987, Timeless Seeds has cleaned, packaged, and marketed certified organic cereal grains, pulse crops, and edible seeds.

David Oien, CEO, is one of the original founders of Timeless Seeds, a company that started selling organic grains and seeds before consumers knew the definition of “organic” or recognized the word “lentil.”

He offers lentils in colors ranging from yellow and red to brown and black, purple barley, and black chickpeas. His grains are as nutritious as they are colorful: the darker the color of the seeds, the higher the level of antioxidants.

(Take a virtual tour of Timeless Seeds here.)

Why Is Organic So Important?

We all know that we should eat more whole grains; everyone from the USDA on down is telling us that. But no one seems willing to tell us that the real key is organic whole grain.

Because conventional grain growers use a huge amount of herbicides to keep the weeds out of their fields and – something most of us don’t know – use even more to “desiccate” (dry out or kill) the plants in order to control the timing of the harvest.(1) Even with the biggest, most sophisticated equipment, it is important to be able to stagger the timing for efficient harvesting.

Herbicides for weed control and desiccation – those approved for “pre-harvest application” – unfortunately can remain on the grain. As can fungicides and pesticides applied to keep the grain from spoiling or being consumed by pests while in storage.

Grains are not washed before milling so the whole grains, berries, groats, flakes, meal, or flour are likely to contain some level of chemicals. Eat organic – it’s the only way to prevent ingesting them.

The Future of Dryland Farming

These farmers and researchers – and the companies processing and marketing their products – depend on knowledge, experience, and training to be successful at “moisture management.”

Learning from each other – the mistakes to avoid and the successes to repeat – links these “grain men” in a closely-related community. Young farmers like Casey and Jacob learn from experienced farmers like Bob Quinn, Daryl Lasilla, and Ole Norgaard.

And together they are all trying new varieties, experimenting with crop diversity, and exploring new grains and pseudograins to ensure that it is possible to grow healthy crops even in dry climates.

As climate change continues to affect agriculture around the world, it is farmers like these who will be able to adapt and succeed.

________________________________________

(1) Desiccation or preharvest weed control? Top Crop Manager Magazine