Publisher’s Note: As residents of the Pacific Northwest, we have salal in our home landscape. Although salal plantings can be aggressive and they can “run wild;” salal is a popular landscaping plant. Yet most of us never look beyond the ornamental beauty to appreciating its regional history and its value as food and medicine. We’ll be looking at our salal with new eyes. Read on and you will too.

________________________________________

Moderator’s Note: It is my privilege this time of the year to present the work of my undergraduate students at the University of Washington. This year I am presenting a series of outstanding blogs by students enrolled in my course on Environmental Anthropology. The large lecture format course introduces students to the field of environmental anthropology, which includes the study of Ethnoecology – the knowledge of ecology developed by indigenous and other traditional place-based peoples. The course also examines contributions from the fields of critical political ecology, which focuses on the role of science in the politics of environmental law, policy, and social movements.

Finally, we study aspects of environmental history, which focuses on the role of human societies – both small- and large-scale – in processes of ecological change and includes analysis of the history of ideas about the quality of the human-environment relationship. Like the class, these blogs seek to bridge all these approaches and more by providing entries that address local place-based knowledge and situate Ethnoecology within the context of politics and history.

So, I am presenting the twenty-second entry in this series, which is a beautifully prepared essay on Salal, a native shade-tolerant shrub that produces little hairy berries and has a long affiliation with First Peoples as a source of food, medicine, lore, and much more. I must say that I love the way in which these students expressed a personal relationship with salal; this was not an object to be gazed on or studied; it is a fellow living being; our relation.

Sadly, the students in this research group found that, while the salal plant has long been part of the food, medicine, and culture of Coast Salish peoples, the arrival of settlers led to the exploitation of the land, forests, and workers. This exploitative paradigm was eventually extended to the salal shrub itself. As the students wisely note:

…the salal industry sounds fairly simple and straightforward: Landowners in Western Washington sell permits to pickers to harvest salal on their lands. The pickers, acting as freelance workers, then take their harvests to the wholesalers, who buy the salal for an insanely cheap price and then sell it the European consumer for much more, reeling in the profits… it is a system based on the exploitation of many (the land, and the workers) for the profit of a few (the wholesalers).

Salal (Gaultheria Shallon)

A NATIVE SHADE-TOLERANT SHRUB FACES INDUSTRIAL EXPLOITATION

Ivy He | Nicole LaBrie | Megan Morgan | Anna Rylko

Indigenous to the Pacific Northwest, the salal plant was harvested in the past and remains important today. Traditionally indigenous people ate the berries and used the leaves for medicines. Recently, the salal plant has evolved into a key component of the floral trade industry.

We are a group of four University of Washington students. We hope our blog post will help to highlight the importance of salal to indigenous people, by examining their understanding of how salal functions in the larger ecosystem. Indigenous groups use Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK), which is a cultural understanding of the natural environment, to foster interactions that benefit plants, animals, and humans. We will also explain how environmental history and political ecology influenced salal and how new groups of people have come to interact with the plant, which is different from the human-plant dynamic a hundred years ago. Our methodology includes research using academic resources, mainstream resources, and personal observations.

Visiting with salal at University of Washington Medicinal Garden

The University of Washington has two large salal shrubs in their medicinal garden. When we first started our research on the plant, we found some preliminary information on the Internet and then we went to the UW farm to make our own observations. Doug, who works at the UW Farm, was enthusiastic to share his knowledge. He said the plant varies in size depending on how much light it receives; it’s taller in shady areas and shorter in sunny spots. Doug showed us to the plants and revealed that he didn’t particularly like the berries.

We were able to spend some time with the salal, writing down observations and taking photographs. Salal is a very striking shrub. It is evident why it has become a commodity for the floral industry. The salal plants in the medicinal garden were about 4 feet tall at the highest point. The stems are red and contrast beautifully with the bright green foliage. The leaves are large and finely serrated around the edges. When light hits the leaves, you can see that there is a main vein running through the middle, while smaller veins branch out from it and tiny mosaic-like pieces fill in the rest. The leaves are also very hardy with few imperfections (blemishes). Some of them are concave and capture water. We later read in the book, Native American Ethnobotany, that some indigenous people folded the leaves like cones for drinking. Although it was late October the salal still had berries. They are a deep purple color and appear to be a little hairy. They looked a little shriveled and tasted dry, a little woody and less sweet than expected.

Environmental history of the salal plant in the Pacific Northwest

Originally used for food and medicinal purposes by indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest, recent years have seen a new found demand for salal. Salal grows rampantly in the Pacific Northwest region, most abundantly at lower elevation and usually in coarse soils. Because of its major presence in the Pacific Northwest bioregion, indigenous peoples originally found many uses for it; including using its berries in cakes or eaten dried and also for medicinal purposes. Its medicinal uses extended over a wide range of ailments including but not limited to, treatment for cuts and burns, an infusion for indigestion, colic and diarrhea, respiratory distress from colds or tuberculosis, and as a convalescent tonic. During the long period when its use was solely due to foraging by indigenous peoples, salal existed abundantly and therefore the Native people invented a large variety of uses for it. However, it is significant to note that they did not abuse its use and therefore salal continued to reproduce abundantly within the Puget Sound bioregion. Indigenous peoples therefore became dependent on the use of indigenous salal.

In recent years, salal has become an important species in the floral trade industry. It is extensively harvested as a special forest product on the Olympic Peninsula and in other areas of the Pacific Northwest. ‘Special forest products’ are products or natural resources that are not the traditional timber and fiber products. There is sparked interest in its sustainability as harvest demands have increased to meet the demands of the floral trade industry. It has been brought into question whether salal will soon become a rare, threatened, or endangered species if the floral industry continues to harvest it with no regard for its availability, rates of reproduction, and use by indigenous peoples. To Western culture, salal is not respected as a ‘way of life’ for food and medicines, but instead as an avenue to create income. While salal is not rare to the Pacific Northwest, but rather grows abundantly throughout, it is now put into question whether it is threatened due to the relatively new demands set upon it by the floral trade industry.

While there have been no real environmental changes that have affected the salal plant, it is instead the anthropogenic effects that threaten its abundance in the Puget Sound bioregion. Human activities, namely the major role salal currently plays in the floral trade industry, threaten to make rare a plant that indigenous peoples have used extensively, and yet respectfully, for many decades.

Ethnobotany, ethnogastronomy, and ethnomedicine of salal

A berry-producing shrub native to North America, salal is particularly found in California, Alaska, and across the Pacific Northwest. An interview conducted in the summers of 2001–2003 on the Olympic Peninsula with 20 salal harvesters indicated that traditional knowledge about the growing environment of Salal helped them to harvest. When the interviewer asked harvesters where to find salal, some responses were lovely but practical:

They live in lowlands, where Douglas fir grows; some lands have a lot of maple trees but salal doesn’t grow under maples…Where trees make shade, the brush is very nice and green.

Learning from Puget Sound Native Americans, many herbalists recommend the leaves of salal for use in tinctures and teas because of their astringent effect. The leaves are still advocated to lower bladder inflammation, treat diseases like heartburn, fever, cramping, and also used to reduce inflammation of the sinuses. Moreover, salal can strengthen the immune function of human body, reach and dredge collateral channels. A common benefit for the public is that the leaves of salal can be made into a poultice to treat insect stings and bites.

In addition to the medicinal purpose, salal is actually an essential food source for many First Nations bands of British Columbia. Aboriginal people eat fresh salal berries or prepare it into jam or preserves. Salal berries are loaded with vitamins and antioxidants that prevent degeneration and help us to live a long and sustaining life. They are such a gorgeous natural treat that can effectively reduce the risk of chronic disease. Admittedly, they are not as tasty as other berries like huckleberries, but they are readily available and have a good flavor. The easiest way to harvest is to pull the entire pink stem of berries off and process them all at once.

The high quality berries were usually kept for family meals and feasts. During feasting, salal berries were eaten with black spoons, which are made from the horn of a Mountain Goat. It is worth mention that the black spoons were only used for this purpose and occasion.

People from the Haida First Nation use salal berries to thicken salmon eggs and sweeten other berries when making jam. It is said that people from the Ditdaht First Nation chewed the young leaves to suppress hunger when they did not have enough food. Many other tribes, especially in Eastern North America, used the leafy branches in pit cooking.

Although people’s lives have been dramatically improved over the last decades by the development of technology; it must be admitted that, health problems are still an acknowledged dilemma. Many people seem to overlook the basic fact: some valuable wild plants were living here thousands years ago. They are better choices to improve blood-sugar levels and weight than real medicine with chemical elements.

Salal recipes

Salal Berry Ice Cream Sandwiches

- 1 pint (about 3 cups) salal berries

- 3/4 cup sugar

- Pinch salt

- 1 tsp. fresh lemon juice

- 1 cup whole milk

- 1 cup heavy cream

- 16 to 20 graham crackers

In a saucepan over medium-high heat, combine berries, sugar, and salt; cook, stirring often, until sugar dissolves, 3 to 4 minutes. Bring to a boil, reduce heat, and simmer 2 to 3 minutes. Add lemon juice. Puree cooked berries in batches, filling blender no more than halfway each time. Strain into a bowl; refrigerate until chilled. Stir milk and cream into berry mixture. Pour into ice cream maker, and freeze according to manufacturer’s instructions. Transfer to freezer until firm enough to hold its shape, about 30 minutes. To assemble, spread about 3/4 cup ice cream on one graham cracker; top with another cracker. Press lightly, and freeze again until firm.

Salal Berry Jam

Makes about three ½-pint jars

- 12 cups salal berries, cleaned

- ¾ teaspoon fresh lemon juice

- 1 to 4 tablespoons sugar, or to taste

In a large saucepan over medium-high heat, cook berries until soft. Strain through a fine-mesh sieve or cheesecloth to extract all the juice. Return berry juice to the saucepan over medium heat; add lemon juice and sugar to taste and cook until sugar is dissolved, 3 to 5 minutes. To can the jam, sterilize ½-pint jars and lids 10 minutes. Fill with hot jam, leaving ¼-inch headspace. Wipe rims with a clean, damp cloth, place lids on and screw them down tight. Place in a boiling water-bath canner with water covering jars by about 2 inches; process 5 minutes. (Begin timing when water returns to boil.) If you do not wish to can the jam, store in the refrigerator.

Ethnoecology and ethnobiology of the salal plant

Native Americans have had a long history with salal. According to literature, the Native American perspective is based on interconnectedness between humans and the natural biological world, which should be in balance. Spirituality and sacredness are associated with the forest. As a sign of respect to the forest, it is important to care for and manage the forest resources. Some of the methods that Native Americans use are planting seeds, transplanting bulbs, plants and trees, pruning trees and plants, modifying soils, using harvest rotation and redirecting water for irrigation to reduce soil erosion, and controlled burning. Traditional ecological knowledge is being lost due to loss of land and limitations placed on native people by the federal government, (Charnley and Fischer).

Although some indigenous people may lose traditional ecological knowledge, an unlikely group is absorbing new knowledge. Salal has recently become part of the profitable floral trade. Harvesters of salal are not generally indigenous to the Pacific Northwest, but immigrants from Southeast Asia and Latin America. Although these people have not learned about salal from their communities, they are developing “local ecological knowledge” after working closely with salal over many years. In Heidi Ballard and Lynn Huntsinger’s study called “Salal Harvester Local Ecological Knowledge, Harvest Practices and Understory Management on the Olympic Peninsula, Washington,” they found that harvesters could articulate ecological effects on salal such as light and canopy cover, elevation and soil moisture. Harvesters with a lot of experience (8 years or more) were able to understand things like multiple species management and resource rotation. Through this study we can find hope that although some knowledge may be lost, it can be regained over time.

Political ecology of salal

The political ecology of salal is inextricably tied to the floral industry. The highest demand for this aesthetic use of salal comes mainly from Europe. The workers who harvest the salal come mainly from Mexico, Guatemala, and Southeast Asia, all coming together in Western Washington and the Olympic Peninsula where salal grows plentifully, where harvest takes place, and where wholesalers set themselves up to reel in the cash.

There is a lot of money to be made in the salal floral industry. The Seattle Times estimates that salal brings $250 billion a year to the Pacific Northwest. Already one fourth the size of Washington State’s famous apple industry, the demand for salal remains high and continues to grow. The problem with this great monetary success of the salal industry is that it comes at the cost of the land and those who harvest the salal, all mass profits going to a tiny fraction of the industry: the salal wholesalers.

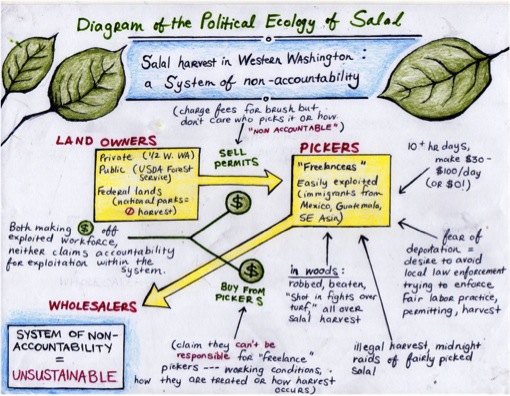

Explained in words, the salal industry sounds fairly simple and straightforward: Landowners in Western Washington sell permits to pickers to harvest salal on their lands. The pickers, acting as freelance workers, then take their harvests to the wholesalers, who buy the salal for an insanely cheap price and then sell it the European consumer for much more, reeling in the profits.

However, the truth of the matter is that it is a system based on the exploitation of many (the land, and the workers) for the profit of a few (the wholesalers). Mapped out below is a diagram that illustrates the kind of system of non-accountability that allows such corruption and abuse to take place within the industry.

In order to make the salal industry sustainable both in terms of workers’ rights and in terms of forest ecology, the State of Washington must face the challenge of creating a system that tracks salal harvests, enforces salal harvesting areas, and ensures the freelance immigrant workers state-required workers rights under labor laws.

Works Cited

Ballard, Heidi L., and Lynn Huntsinger. “Salal Harvester Local Ecological Knowledge, Harvest Practices and Understory Management on the Olympic Peninsula, Washington.” Human Ecology 34.4 (2006): 529-47. University of Washington Libraries. Web. 30 Oct. 2012.

Bleakney, Gregg. “Pirates of the Rainforest.” Sierra, August 2012. http://www.sierraclub.org/sierra/201207/olympic-national-park-trees-poachers-198-2.aspx (accessed November 19, 2012).

Charnley, Susan, A. Paige Fischer, and Eric T. Jones. Traditional and Local Ecological Knowledge about Forest Biodiversity in the Pacific Northwest. Portland, OR: U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station, 2008. University of Washington Libraries. Web. 1 Nov. 2012.

Gasteyer, S., and Flora, C. B. (2000). Measuring ppm with tennis shoes: Science and Locally Meaningful Indicators of Environmental Quality. Society & Natural Resources 13(6): 589–597.

Moerman, Daniel E. Native American Ethnobotany. Portland, Or.: Timber, 1998. Print.

“Salal Harvester Local Ecological Knowledge, Harvest Practices and Understory Management on the Olympic Peninsula, Washington – Springer. Salal Harvester Local Ecological Knowledge, Harvest Practices and Understory Management on the Olympic Peninsula, Washington – Springer. N.p., 01 Aug. 2006. Web. 06 Nov. 2012.

Seattle Times “Salal Berry Jam” http://community.seattletimes.nwsource.com/archive/?date=20030709&slug=salal09 (Written July 9, 2003; Accessed Novemeber 14, 2012 at 10:49AM, www.seattletimes.com)

Seattle Times Article: “Wild, wonderful Northwest berries” http://community.seattletimes.nwsource.com/archive/?date=20030709&slug=berries090 (Written June 9, 2003; Accessed November 14, 2012 at 11AM, www.seattletimes.com)

S., Dee, and Jenn Walker. WiseGeek. Conjecture, 22 Sept. 2012. Web. 17 Oct. 2012. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bp5oD1NNMcY (Gaultheria shallon)

Welch, Craig. “A War in the Woods.” Seattle Times, June 06, 2006. http://seattletimes.com/html/localnews/2003042206_salal06m.html (accessed November 19, 2012).

________________________________________

About Devon G. Peña

A lifelong activist in the environmental justice and resilient agriculture movements, Devon G. Peña is a Professor of American Ethnic Studies, Anthropology, and Environmental Studies at the University of Washington in Seattle. He also works on the family’s historic acequia farm in San Acacio, Colorado.

A lifelong activist in the environmental justice and resilient agriculture movements, Devon G. Peña is a Professor of American Ethnic Studies, Anthropology, and Environmental Studies at the University of Washington in Seattle. He also works on the family’s historic acequia farm in San Acacio, Colorado.

A pioneering interdisciplinary research scholar and widely-cited author, his most recent books include Mexican Americans and the Environment: Tierra y Vida (U. of Arizona Press, 2005) and The Oxford Encyclopedia of Latinos and Latinas in the United States (senior editor, Oxford University Press, 2005).

Dr. Peña is the Founder and President of The Acequia Institute, the nation’s first Latina/o charitable foundation dedicated to supporting research and education for the environmental and food justice movements.

Read this article as it was originally published here.

I find Salal ridiculously easy to cultivate in Olympia, Washington. Why is cultivation not a sustainable alternative to wild harvesting?

Thanks for a great educational write-up on Salal and its uses. Please tell me where I can find exact instructions for making tea and infusions with the leaves. I live in Oregon, and the bush is growing wild right in my back yard. Thank you.

Frieda,

You might try the instructions here: http://wildfoodsandmedicines.com/salal/

You can make “fruit leather” from the berries and tea from the leaves. The instructions are easy.

Gail N-K

Thank you for the informative article. I live in the NW and I queried eating salal since I have always heard the indigenous people ate it. That being said, I question the 250 Billion estimate for salal harvesting. Seriously? Billion? I also question the assumption of exploitation that is defaulted to throughout the article. I would have an easy time describing all employment as exploitation using the loose parameters that are applied here. I wonder if there was too hard an emphasis from the authors on attaining relevance for their article by “discovering” their controversial assumptions. As a parent,I appreciate the energy and motivation that is inherent In our youth, especially those like these students, but as an adult and a teacher I think it is also important to share the experience and wisdom that comes with age.